Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 18

Ethical Gaps in Ophthalmology in the United States

Authors Browning DJ

Received 26 April 2024

Accepted for publication 27 August 2024

Published 6 September 2024 Volume 2024:18 Pages 2539—2544

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S475660

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

David J Browning

Department of Ophthalmology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

Correspondence: David J Browning, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC, 27157, USA, Email [email protected]

Purpose: To highlight gaps in the professional ethics of ophthalmology.

Design: Perspective.

Methods: Presentation of problematic cases in ophthalmologic ethics with juxtaposition of ethical, legal, and conscientious viewpoints informed by relevant literature.

Results: What is legal, ethical, and conscientious overlap but are not identical. Professional ethical guidelines, when they exist, are stricter than what the law requires, but are silent on several contemporary controversies. Conscientious guidelines can vary from loosest to strictest as they apply to individuals with wide variability. The relationship of ophthalmology to society changes, and ethical guidelines lag for some of the interactions.

Conclusion: The rules of ethics for ophthalmology need to be updated and evidence of activity and oversight made public. Failure to do so invites greater external regulation.

Keywords: ethics, ophthalmology, law, conscience, free press, conflict of interest, financial disclosure

Ethics is the field of philosophy dealing with what is right and wrong. Ethical standards depend on historical eras, cultural context, and religious background. They are subjective and changing. For example, Lucien Howe was president of the American Ophthalmological Society in 1901 and endowed the Howe Medal of the society. He, and others of his era, believed in eugenics and advocated forced sterilization of those with genetic mutations leading to congenital blinding diseases.1 In the contemporary world, ethical analysis has changed. There is no government, culture, or religion in the world where forced sterilization for a genetic mutation is considered ethical.

Laws are rules set by governing bodies that regulate behavior. Ethical and legal behaviors overlap but are not identical. For example, it is both illegal and unethical to purchase a foreign version of ranibizumab at a low price and then administer it to a patient in the United States as Lucentis and bill Medicare at a higher price, pocketing the difference.2 However, there exist unethical behaviors that are legal and illegal behaviors that are ethical. There is no ethical violation if an ophthalmologist not on duty in Florida uses recreational marijuana, but it is illegal to do so. On the other hand, it is legal for an ophthalmologist to accept rebates from pharmaceutical companies in the purchase of intravitreal drugs,3 but it is unethical to allow the rebate to affect his prescribing behavior.4 As with ethics, laws change over time. For example, smoking marijuana by adults is legal in Colorado, but was illegal before 2012.5

Because it can be impossible to discern a causal link between behavior and intention, establishing an ethical violation can be more difficult than violating law. An ophthalmologist who chooses to use a drug of equivalent efficacy, but a larger rebate, can assert that the basis for the choice is on-label status, or non-compounded origin, or reduced medicolegal concern, rather than inurement, and it would not be possible to prove otherwise. In other cases, evidence exists, such as a temporal correlation between prescribing behavior and a rebate change but is inaccessible as confidential practice information. A second-order ethical dilemma can thereby arise. An ophthalmologist within a group can witness unethical behavior yet be bound by confidentiality from bringing it to account.

Conscience refers to the internal sense of right and wrong, one’s moral compass. Whereas ethics and laws apply to groups of people, conscience applies to individuals. The boundaries of the set of behaviors compatible with one’s conscience are fuzzier than those for ethical and legal behavior. Conscience varies from person to person and within the same person over time. Moreover, conscience refers to a feeling, whereas ethics and laws refer to actions. Although fuzzy, conscience is essential, because the oversight of ethics boards and legal enforcement is intermittent and piecemeal, but the physician’s conscience is his constant companion.6

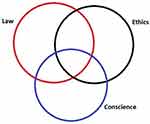

There are behaviors that are legal and do not violate ethics yet can trouble one’s conscience. For example, an ophthalmologist’s group may accept pharmaceutical company rebates and allow the use of intravitreal injectable drug samples, and one may have voted against the group’s decision and been outvoted, yet if one stays in the group, one’s conscience may be conflicted according to the principle of guilt by association. As another example, a hospital may have a rule that a case cannot be booked for surgery with a plan to explant a dislocated intraocular lens implant and simultaneously implant a secondary intraocular lens on grounds that reimbursement to the hospital is less than a two-procedure plan – one operation to explant the dislocated implant and a second one to implant the replacement implant. The ophthalmologist may disagree yet have no other options as to where to operate and the patient may not be able to travel elsewhere for care. Figure 1 illustrates schematically the relationships of ethics, laws, and conscience.

|

Figure 1 Venn diagram sketching the relationship of laws, ethics, and conscience. They are not coincident, not invariable in time, nor across people. |

Many medical situations are unclear from the standpoints of ethics, laws, and conscience. For example, in the process of in vitro fertilization multiple embryos are produced and frozen. If the frozen embryos are destroyed there are people who believe that murder has been committed.7 Their view is that the embryo is a human being at an early stage of development. There are others who believe that there is nothing ethically wrong with the action. Their view is that the embryo is a clump of cells that is nonviable without special technology. Laws differ on the matter across countries.8 The ethics of reproductive endocrinologists’ practices are being challenged, the applicable law is in flux, and the consciences of the involved patients and physicians vary on the matter.

Another current area of ethical unclarity involves the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) movement, which has sparked controversy in medical training and ophthalmology over ethical issues. Proponents argue that medical school and ophthalmology residency admissions discriminate against certain groups of applicants by using standardized test scores.9 They propose that patients be cared for by doctors trained in cultural as well as technical competence and trained to overcome alleged unconscious bias.10 Opponents of DEI in medical training contend that these efforts undermine meritocracy, are divisive, based on assertions without evidence, and waste resources.11 Other ethical issues such as air travel to medical meetings with effects on climate and generation of medical plastic waste with environmental harm are currently under debate. For these topics it would be foolish to prematurely publish ethical rules which might need to be retracted when the controversies are resolved.

One branch of ethics concerns professions such as ophthalmology. Professional ethics are codes of conduct that are developed and to which members of the profession are held accountable The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has rules of ethics published on its website that are enforceable on its members. These include:

1). Necessity of informed consent for medical and surgical procedures.

2). Prohibition against misrepresentation of services and charges.

3). Prohibition against altering the medical record.

4). Prohibition against an ophthalmologist’s economic interest influencing clinical judgment and practice.

5). Disclosure of conflicts of interest by ophthalmologists to patients, the public, and colleagues.4

Professions have an implied social contract in which they are granted privileges in return for attending to responsibilities. To the extent that society deems self-regulation effective, external regulation is withheld. When self-regulation is overlooked, society reserves the right to impose external regulation.12 Therefore, periodically, ophthalmologists need to examine whether we live up to our self-set rules of ethics. This Perspective contends that rules 1–3 are generally followed. We do less well regarding rules 4 and 5 and can and should improve. Moreover, there are some ethical situations that the current rules do not address. Some ways that we could improve are suggested and some dilemmas in need of guidance are indicated.

Ophthalmologists recognize that accepting payments from drug and medical device companies can influence clinical recommendations.13 Therefore, before ophthalmologists are allowed to speak at Academy meetings, they must disclose the presence or absence of financial relationships.

However, influence is not a dichotomous variable that is either present or absent. It is a continuous variable. The larger a financial relationship is, the greater the probability that the relationship influences the ophthalmologist’s clinical judgment and practice. One can go to the Sunshine Act website and check the value of payments made to ophthalmologists by drug and medical device companies.14,15 The clinical judgment of an ophthalmologist who has received payments exceeding 100,000 dollars in a year (many such examples exist) is more likely to be influenced by the payment than will the judgment of one receiving 100 dollars in a year.16,17 Yet, under existing Academy guidelines the disclosure slide for the two ophthalmologists can look identical to the audience.

Despite flaws, at least financial disclosures between ophthalmologists at meetings are required and policed in their rudimentary forms. Such is not the case in relationships of ophthalmologists and their patients. This is egregious, because of the asymmetry of knowledge in that relationship.18 An ophthalmologist at a meeting has enough knowledge apart from a financial disclosure slide to assess whether bias is present in the presentation. In fact, the question is routinely posed in the post-presentation feedback whether the speaker showed bias. This is not the case when an ophthalmologist faces his patient. The patient is unaware that the ophthalmologist pockets an additional sum should a more expensive drug A be recommended than a less expensive drug B of equal efficacy. It is uncommon for these discussions to occur, and the AAO does not attempt to enforce disclosure to patients as it does disclosures to ophthalmologists even though it says it requires disclosure to patients.4

What might we do to improve the situation?

For presentations at meetings, instead of a dichotomous financial disclosure slide and the speaker’s opinion as to relevance, consideration should be given to a calibrated slide. This slide would list the total of payments made to the speaker from the Sunshine Act website. It would also show a histogram with the top 10 payers to the speaker and their respective amounts. Each subsequent slide of the presentation would have in the corner the figure for the total payments.

Training programs should not allow drug and medical device companies to pay for dinners at restaurants for journal clubs, fluorescein conferences, and surgical conferences. Ethical norms for ophthalmologists are instilled in training. A higher standard should prevail there even if it is legal outside a training program setting to have sponsored dinners. In private practice, paid speakers should not just be required to acknowledge payment but should have on each slide of the presentation the amount paid to provide the speech in addition to the total amount paid to the speaker from the Sunshine Act website. The example of the American Ophthalmological Society is the best. Its annual meeting is paid for by the members. No industry payments subsidize the meeting.13

Ophthalmological entities that have a presence on the internet should have a tab referring to financial disclosure; this should be incorporated into the AAO’s rules of ethics. It should require disclosure regarding acceptance of rebates from drug and medical device companies and list the sum of the rebates accrued annually for the past 5 years broken down by the payer. Academic training programs do not reap the financial rewards of drug rebates that private practices do, but they can avail themselves of the federal 340B drug discount program established in 1992 whereby they pay prices 25–50% lower than the average wholesale price for expensive medications, receiving market prices when they bill payers, and using the difference to fund operations.19 Their community practice affiliates can profit from rebate programs just like any private practice.3 Both types of financial inurement should be made public. To avoid the appearance of influence buying, ideally the rebates and mark-ups should go toward patients, not physicians. For instance, rebates and mark-up revenue could be allocated to the purchase of patient bad debt at discounted rates, which could be forgiven. Alternatively, these revenues could go toward research and development rather than the prescribing physicians’ income.

A less formal, but no less powerful force influencing rectitude in the ethical decision-making of ophthalmologists is a free press. I have participated in meetings in which decisions with ethical implications were considered through the lens of what is generically termed the New York Times test. In that test, the participants ask, “What if this comes out in the New York Times (substitute the applicable local newspaper)? How would this affect our practice?”20 Sometimes it leads to abandonment of a questionable action. Other times, it leads to disguise. For example, the cash payment for a premium intraocular lens may be redirected using a group accounting rule from direct flow to the surgeon’s bottom line, to general reduction of group overhead, to deflect criticism of conflict of interest. In the United States, ophthalmic ethics benefits from freedom of the press. In countries with a press subservient to the government the effect on medical ethics works in reverse. For example, Wuhan ophthalmologist Li Wenliang was censured for ethically alerting the public to the initial Wuhan Covid-19 outbreak.21 Dr. Angelina Guskova attempted to warn the Russian public about the medical dangers of fast track development of the atomic power industry in the years preceding Chernobyl but was forbidden from publishing her observations.22

United States governmental payments to ophthalmologists are large and rising. Most of these are payments for services to patients, but with the Covid-19 pandemic, the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) and Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) provided funds to pay employees and cover practice expenses when economic life was disrupted. The Office of the Inspector General estimates that $200 billion of the $1.2 trillion disbursed was used fraudulently.23 Cases of fraud include ophthalmic practices.24,25 However, beyond fraud, there is the issue of the proper recipients of the funds. What are the ethics of ophthalmologists using the PPP money to supplement their own incomes in addition to their employees’? One might contend that the money should go only to furloughed employees, as intended by the legislation, not to the ophthalmologist owners to keep their incomes at pre-pandemic levels, but the AAO rules of ethics do not cover such scenarios.

In the United States, ophthalmologists frequently renegotiate contracts with insurers. Sometimes these come to an impasse with the ophthalmologists asking for higher reimbursement and the insurer for lower. Is it ethical to ask the patients of the practice to lobby in favor of the ophthalmologists? One might contend that this is unethical, but the AAO rules are silent on the matter. An update to include social, cultural, and business aspects to ophthalmology professional ethics would be welcome.

Examples of ethical dilemmas not covered by professional guidelines are dependent on context. In countries with nationalized health insurance, ophthalmologists do not negotiate with insurers. However, one could consider that an ethical issue arising in that context, but not the United States, would be the determination of the cost per quality adjusted life year threshold that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom considers acceptable for coverage of an ophthalmic treatment. There is no such threshold specified my governmental payers of health care in the United States. Thus, discussions of ethical gaps in ophthalmology are rooted in society. This Perspective concerns the situation in the United States.

Ethical decision making comes up every day in an ophthalmologist’s life. Our professional culture is not a talisman that makes us immune to human ethical failings; rather it is a muscle that atrophies if not used. Moreover, the existence of a professional webpage devoted to ethics does not constitute evidence of its efficacy.4 The AAO needs to publish use statistics on ethics committee activity so that the interested profession and public can see what the level of oversight is. Currently, there is no transparent way to review AAO ethics committee activity, rules reviews, dismissals, and enforcement actions, nor to see if ethical violations have led to repercussions. We owe it to ourselves to review whether our rules of ethics guide our behavior and nudge our consciences in the direction we aspire to go, and if they do not, to revise them. We owe it to our patients to make our ethical rules strong, contemporary with the evolution of ethical thinking, and public. If we do not, our ethics become lip service and we can expect more external regulation.

Table of Contents Statement

There are ethical gaps in ophthalmology that bear attention; American Academy of Ophthalmology rules of ethics need updating to address modern ethical conundrums.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

Dr. David Browning receives book royalties from Springer Inc. He owns stock in Zeiss Meditec Inc. Neither of these lies within the scope of the present work. The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Ravin JG, Stern AM. Lucien Howe, hereditary blindness, and the eugenics movement. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(7):924–930. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.137

2. Ophthalmologist pleads guilty to using misbranded medication. 2021. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/usao-wdnc/pr/ophthalmologist-pleads-guilty-using-misbranded-medication.

3. Pollack A. Genentech offers secret rebates for eye drug. NY Times. 2010.

4. Code of Ethics of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2023. Available from: https://www.aao.org/education/ethics-detail/code-of-ethics.

5. Legal marijuana use in Colorado. 2024. Available from: https://cannabis.colorado.gov/legal-marijuana-use-in-colorado.

6. Miola J. Making decisions about decision-making: conscience, regulation, and the law. Med Law Rev. 2015;23(2):263–282. doi:10.1093/medlaw/fwv010

7. The Alabama Supreme Court’s Ruling on Frozen Embryos. 2024. Availabe from: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2024/the-alabama-supreme-courts-ruling-on-frozen-embryos#:~:text=At%20the%20trial%20court%2C%20this,could%20bring%20under%20that%20act.

8. Dickens BM. The use and disposal of stored embryos. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;134(1):114–117. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.04.001

9. Powell MS, Parker QE, Rhodes LL, Mehta ST. Will residency program directors look at my United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score during the 2022–2023 application cycle? A national survey of program directors. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29483. doi:10.7759/cureus.29483

10. Advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in medical education. secondary advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in medical education. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/about-us/equity-diversity-inclusion/advancing-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-medical-education.

11. Ban DEI quackery in medical schools. Wall Street J. 2024.

12. Cruess SR. Professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:170–176. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000229275.66570.97

13. Lichter PR. Debunking myths in physician-industry conflicts of interest. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(2):159–171. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.007

14. Learn about the financial relationships that doctors and other healthcare providers have with drug and medical device companies. Secondary learn about the financial relationships that doctors and other healthcare providers have with drug and medical device companies. 2024. Available from: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/.

15. Sayed A, Ross JS, Mandrola J, Lehmann LS, Foy AJ. Industry payments to US physicians by specialty and product type. JAMA. 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.1989

16. Mitchell AP, Trivedi NU, Gennarelli RL, et al. Are financial payments from the pharmaceutical industry associated with physician prescribing?: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):353–361. doi:10.7326/M20-5665

17. Yeh JS, Franklin JM, Kesselheim AS. Payments to physicians, prescribing rates, and more appropriate conclusions-reply. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1577. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5802

18. Browning DJ, Greenberg PB. Quantifying conflict of interest in the choice of anti-VEGF agents. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:1403–1408. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S298575

19. Conti RM, Bach PB. The 340B drug discount program: hospitals generate profits by expanding to reach more affluent communities. Health Aff. 2014;33(10):1786–1792. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0540

20. Kafaee, M, Taqavi, M Technology and Society The New York TImes Test: an intersubjective reconsideration https://technologyandsociety.org/the-new-york-times-test-an-intersubjective-recondiseration/

21. Death of coronavirus doctor Li Wenliang becomes catalyst for ‘freedom of speech’ demands in ChinaSouth China Morning Post. South China Morning Post. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3049606/coronavirus-doctors-death-becomes-catalyst-freedom-speech.

22. Higginbotham A. Midnight in Chernobyl. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2019:221.

23. COVID-19 Pandemic EIDL and PPP loan fraud landscape. Available from: https://www.sba.gov/document/report-23-09-covid-19-pandemic-eidl-ppp-loan-fraud-landscape#:~:text=We%20estimate%20that%20SBA%20disbursed,disbursed%20to%20potentially%20fraudulent%20actors.

24. Ophthalmologist pleads guilty to seven-year healthcare fraud scheme and to defrauding SBA program intended to help small businesses during COVID-19 pandemic. 2021. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/ophthalmologist-pleads-guilty-seven-year-healthcare-fraud-scheme-and-defrauding-sba.

25. Seattle doctor found guilty of fraudulently obtaining millions of dollars from COVID-19 relief programs. 2023. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/seattle-doctor-found-guilty-fraudulently-obtaining-millions-dollars-covid-19-relief-programs.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.