Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 17

Predictors of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Acceptability Among Physicians, Their Knowledge on Cervical Cancer, and Factors Influencing Their Decision to Recommend It

Authors Alosaimi B, Fallatah DI, Abd ElHafeez S, Saleeb M, Alshanbari HM, Awadalla M , Ahram M, Khalil MA

Received 27 June 2024

Accepted for publication 8 November 2024

Published 13 November 2024 Volume 2024:17 Pages 5177—5188

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S484534

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Charles V Pollack

Bandar Alosaimi,1 Deema I Fallatah,2 Samar Abd ElHafeez,3 Marina Saleeb,4 Huda M Alshanbari,5 Maaweya Awadalla,1 Mamoun Ahram,6 Mohammad Adnan Khalil7

1Research Center, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh Second Health Cluster, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia; 3Epidemiology Department, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt; 4MARS Global, Covent Garden, London, UK; 5Department of Mathematical Sciences, College of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 6Department of Physiology and Biochemistry, School of Medicine, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan; 7Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Aqaba Medical Sciences University, Aqaba, Jordan

Correspondence: Bandar Alosaimi; Mohammad Adnan Khalil, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Introduction: In Saudi Arabia, the HPV vaccine is administered to young females through school-based immunization programs; however, the program’s efficacy depends on parental consent, with physicians acting as primary determinants in parental decision-making regarding HPV vaccination.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, we recruited 128 physicians and assessed their knowledge and attitudes toward cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine, and unraveled predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability and factors that would influence recommending the vaccine.

Results: Although the major factor that influenced recommending the vaccine negatively was the fear of vaccine side effects, a positive influence of the physician’s personal reading (91%), recommendations from colleagues (88%), and government directives (87%) provided reassurance and increased confidence in recommending the vaccine. Longer clinical experience and institutional awareness were found to be a predictors of favorable recommendation of HPV vaccination. Physicians in vaccine-related medical specialty with more than 4 years of experience were 5 to 6 times more likely to have positive attitude and better knowledge regarding HPV and HPV vaccination. A notable finding was that participants who reported knowing a woman suffering from cervical cancer had more positive attitudes compared to those who did not.

Discussion: This study identified physicians’ personal reading, peer recommendations, and government directives as factors affecting the physicians’ decision to recommend HPV vaccine, and found that longer clinical experience and institutional awareness were predictors influencing physicians to recommend the vaccine. It also emphasizes on the influence of healthcare providers in promoting the HPV vaccination and the need for designing interventions targeting specific demographic and professional groups that would be more effective in improving better knowledge and promoting positive attitudes towards these critical public health issues.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, cervical cancer, human papillomavirus, factors, physicians, knowledge, attitudes

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a family of closely related, non-enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses, with over 200 varieties, including types 6, 11, 16, and 18. The most common infection is of the genital tract.1 High-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are oncogenic variants that precipitate more than 99% of Cervical Cancer cases (CC) worldwide.2 CC is one of the most prevalent gynecological malignancies, and the fourth most common cancer type in women worldwide, following breast, colorectal and lung cancers, with over 662,000 new cases and more than 348,000 related deaths annually.3 In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a call for immediate action to eradicate cervical cancer. Although the prevalence of HPV in Saudi Arabia is relatively low compared to the global average of 11–12%, and cervical cancer represents approximately 2.6% of all cancers in women in the country, the mortality rate associated with cervical cancer remains a significant concern.4–6 This is particularly worrying given that many cases are diagnosed at advanced stages, primarily due to inadequate screening coverage and limited public awareness of the disease.

CC is a preventable and curable disease, primarily by prevention, early diagnosis, application of various screening methods, and treatment measures.7 Currently, there are three vaccines designed to prevent cervical cancer by targeting high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, which are responsible for the majority of cervical cancer cases worldwide.8 When these vaccines are given early, especially before becoming sexually active, they significantly lower the risk of developing cervical cancer later in life.8 It is important to note that HPV vaccination is a key preventive measure, but it is distinct from the process of early detection, which is achieved through cervical cancer screening methods such as Pap smears and HPV DNA testing.9 Screening aims to identify pre-cancerous lesions or early-stage cancers in women who may have already been exposed to HPV. In Saudi Arabia, where the uptake of the HPV vaccine is still growing, it is crucial to emphasize that vaccination and screening work together to reduce the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer.10 Public health initiatives must prioritize both increasing vaccine coverage and maintaining effective screening programs to successfully lessen the burden of cervical cancer.

Several studies have addressed the issue of poor HPV vaccine uptake and have identified factors contributing to low uptake, including limited awareness of the disease and vaccine, cost barriers, sociocultural barriers, vaccine availability, lack of social mobilization, and misconceptions about its novelty.11 It was also found that health care providers’ awareness, attitudes, and recommendations are crucial for the uptake of HPV vaccines among adolescent women worldwide. This is because physicians are the primary point of contact with patients, as they provide patient care, as well as health education.11 Many studies worldwide report the influence of physician recommendations on parent’s decisions to adopt HPV vaccination.4,11,12

The demographic in Saudi Arabia is predominantly Arab-Muslim, with conservative views on sexual behavior and related health issues, such as HPV-induced Cervical Cancer. Notwithstanding, the Ministry of Health officially introduced the HPV vaccine in 2020. While vaccine coverage is unclear, multiple surveys have been conducted since 2020 to estimate take-up. Akkour et al reported that only 2% of Saudi women received the HPV vaccine.12 A recent study conducted in the Eastern Province to measure awareness and knowledge of the HPV vaccine among females and males discovered that less than 4% of participants had received the vaccine.13 Another study conducted in Riyadh revealed that a large percentage (70%) of Saudi parents had never heard of the HPV vaccine.14

In Saudi Arabia, the HPV vaccination program was only established in 2020. HPV vaccine is given to females within school-based immunization programs from 9 to 13 years of age. However, the success of the program largely depends on the parents’ approval, and physicians are major influencers in the decision-making process of vaccination for HPV. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of physicians toward cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine, and unraveled the factors that would influence recommending the vaccine.

Methodology

Study Design and Setting

This is a cross sectional study that was conducted between 7/8/2023 and 24/10/2023 among physicians who work for the Second Health Cluster in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Sample Size and Study Population

The study assumed that 94% of physicians have good knowledge about HPV and its relationship to cervical cancer in Saudi Arabia,15 using a precision of 5.0%, an alpha error of 0.05, and a non-response rate of 10% The minimum required sample size was 100 participants and 130 physicians were recruited in the research. Out of a total of 130 participants, 128 consented to participate in the study, while 2 declined. This results in a high response rate of approximately 98.46%, indicating strong interest and willingness among the participants to engage in the research. We included all physicians whether directly influencing the decision of HPV vaccine uptake or not. The “vaccine-related medical specialty” group included the following primary specialties: Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Infectious Diseases. In addition, physicians from various other medical specialties such as Anesthesiology, Dermatology, and Radiology were also included.

Data Collection Tool

We used an evaluated pre-validated questionnaire to assess the knowledge, attitudes and influential factors influencing physicians about HPV, cervical cancer and the HPV vaccine (in supplementary: questionnaire). The final version of the questionnaire was verified by three of the authors (identified as S.A., M.A.K., and M. Ahram) and used for the manuscript. The questionnaire items were divided into four sections. The first section collected basic sociodemographic data and gauged participants’ familiarity with cervical cancer and sources of the HPV vaccine. The second section contained 16 items with a choice of answers –“Correct”, “False”, or “Do not Know” - to evaluate knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV and the HPV vaccine. The third section included 15 items, each with five response options based on a Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”, designed to assess attitudes towards cervical cancer, HPV and the HPV vaccine. The fourth section consisted of 13 items intended to identify factors influencing the decision to receive the HPV vaccine, using a Likert scale from “Strongly Positive” to “Strongly Negative”. Knowledge items were scored as follows: −1 for “Do not Know”, 0 for “False”, and 1 for “Correct”. The correct answers were weighted, according to the difficulty of each item. The maximum score in the knowledge section was 51, with a higher score indicating greater knowledge. The attitude questions in section three were scored using a five-point Likert scale: 1 point for “Strongly Disagree”, 2 points for “Disagree”, 3 points for “Not Sure”, 4 points for “Agree”, and 5 points for “Strongly Agree”. The maximum score in the attitude section was 75, with a higher score indicating a more positive attitude. Finally, physicians were asked about factors influencing their decision to recommend the HPV vaccine. The effect of each factor was measured by a 5-point scale, ranging from a very positive to a very negative effect.

Data Management

The data distribution of the questionnaire was analyzed using visual identification of a normal distribution via a QQ plot. Quantitative variables were summarized as the median [interquartile range (IQR)] for non-normally distributed data, while qualitative variables were presented as percentages and frequencies. Knowledge and attitude scores were categorized based on median values. Participants scoring above or equal to the median value of 38.5 were deemed to have good knowledge, and those scoring below were considered to have poor knowledge. Similarly, those scoring above the median value of 56 were considered to have a positive attitude, while those scoring below or equal to the median were deemed to have a negative attitude. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test for bivariate analysis to compare age with better knowledge and positive attitude categories. The Chi-squared test was used to compare knowledge and attitude categories with the study population’s baseline characteristics. Two multiple logistic regression models were built to identify the predictors of better knowledge and positive attitude. All potential confounders were included in the analysis. The final models included variables such as age, sex, marital status, education level, medical specialty, frequency of reading medical papers, being a parent of girls aged 10–18 years, knowledge about women diagnosed with cervical cancer, and hearing about cervical cancer from their organization. The knowledge category was added to the multiple logistic regression model to identify attitude predictors. We used the R package for the analysis. The tests were two-tailed, and p values <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Sum of Scores of the Knowledge and Attitude Domains and the Calculation of the Cutoff Points

The sum of scores were calculated for all the 16 questions of knowledge as well as the 15 questions of attitude. The median, which represents the middle value of the sum of scores after sorting them ascendingly, was used as our cutoff point. The median values were 38.5 and 56 for the knowledge and attitude domains respectively. People with a median sum of score lower than 38.5 were considered having lower knowledge and those with a sum of score of 38.5 or above were considered having high knowledge. The same technique was used to categorize the sum of scores of the attitude domains. After the categorization, we used both binary variables as our main outcomes.

We chose this approach for two primary reasons. First, the sum of scores could not be treated as a continuous variable for conducting a valid linear regression analysis, as key assumptions such as normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were not satisfied. Second, categorizing the variables and conducting both bivariate analysis and logistic regression allows for clearer comparison between the “high” and “low” groups in terms of their acceptability of the HPV vaccine. This method directly addresses our research question, enhancing the interpretability of the results for the readers.

Results

Study Population Characteristics

A total number of 128 physicians were enrolled in the study median (IQR) age of 30 (26–28) years 30 years. Nearly half (48%) were married, and there was an almost equal female to male ratio (1.04:1). Among the participants, 67% were physicians practicing in vaccine-related medical specialty, and the majority (92%) were employed by the public sector. Over half (52%) had at least 4 years of experience and 41% reported reading research articles at a moderate frequency. More than one-third (37%) had at least one child, 29% had at least one daughter, and 15% had a daughter aged between 10–18 years. Only 30% personally knew of a woman suffering from cervical cancer, while 49% reported receiving information about cervical cancer at their workplace (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants |

The median (IQR) age of physicians with good knowledge was significantly higher than those with bad knowledge [35 (27, 41) versus 28 (26, 33)]. Physicians who were practicing in vaccine-related medical specialty had good knowledge (52%) compared to 14% with bad knowledge. It was found that 64% of doctors with > 4 years of experience had good knowledge compared to 31% with bad knowledge. Additionally, there was significant association between the educational level and good knowledge. Overall, there was no significant associations between baseline characteristics and attitude category (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Comparison of the Baseline and Demographic Characteristics Between Those with “Bad” versus “Good” Knowledge as Well as “Negative” versus “Positive” Attitude |

Knowledge About the Cervical Cancer, HPV, and HPV Vaccine

The total median knowledge score was 38.5 (IQR: 23, 47), ranging from −16 to 51. This score indicates that participants responded with “True” for many items. More than half of the participants correctly answered all questions regarding cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine. However, only 38.3% selected the right answer for, “There is currently a treatment to cure HPV infection” (Supplementary Table 1). When asked about their sources of information about the HPV vaccine, 77% learned about it at university, 58% from the media, and 63% from reading papers and attending conferences. A smaller percentage (33%) learned about it from friends, while 11% had not heard about it at all. Physicians were also asked about their sources of information on the HPV vaccine (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Sources of information about the HPV vaccine among the study participants. |

Attitudes About Cervical Cancer, HPV, and HPV Vaccine

This study determined physicians’ attitudes towards the HPV vaccine. The total median attitude score was 56 (IQR: 52, 61), ranging from 43 to 75. Between 62% and 93% of study participants agreed or strongly agreed with most items in the attitude domain. Only 18.5% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I must encourage my students/daughters to take the HPV vaccine”. 29% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I will not recommend the HPV vaccine if it has adverse effects”. Although 38% agreed or strongly agreed with “I must avoid talking about sexual education with my students/daughters”, almost the same proportion (37%0 disagreed with this statement (Figure 2 and supplementary Table 2).

|

Figure 2 Distribution of the study participants’ levels of agreement with different items of the attitude domain. |

The questions included their belief in the vaccine’s 1) Effectiveness; 2) Safety; and 3) Potential side effects. Physicians were asked if they would support factors such as 3) avoid discussing STDs with patients; 4) encourage female patients to receive the vaccine; 5) conduct awareness campaigns; 6) allow girls to obtain the vaccine without parental permission; 7) and include the “Sexual Education” course in school curricula. They were also asked to 8) assess the impact of religious fatwa; 9) the impact of medical recommendations; 10) their experience with COVID-19 vaccine, and 11) how they would advise women to protect against Cervical Cancer. They were also asked 12) whether they would make the same recommendations to their own families as to their patients; 13) if religious scholars objected to the vaccine; 14) if the vaccine had side effects; and 15) if they believed the vaccine could lead to societal disintegration because it would introduce concepts of sexual freedom.

Predictors of Better Knowledge and Stronger Positive Attitudes for Cervical Cancer, HPV, and HPV Vaccine

We analyzed the data to identify predictors of better knowledge and positive attitudes of physicians towards cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine. Physicians with vaccine-related medical specialty were 5 times more likely to have good knowledge compared to those with general medical specialties (OR: 4.93, 95% CI: 1.56–17.28). Furthermore, a statistical significant association was observed between the attitude and knowledge of physicians who were practicing in vaccine-related medical specialty compared to physicians who have general medical specialty (OR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.05–0.74). Physicians with more than 4 years of experience are almost 6 times more likely to possess better knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV and the HPV vaccine than those with 4 years of experience or less (OR=5.94; CI=1.29–29.14). Participants who reported being informed about cervical cancer by their institutions were three times more likely to possess good knowledge compared to those who had not been informed by their institutions (OR=2.794; CI=1.11–7.30). Overall, individuals with high level of knowledge are also 4.73 times more likely to have a positive attitude compared to those with a low level of knowledge (OR=4.73; 95% CI=1 1.86–13.11) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Predictors of Knowledge and Attitude Towards Cervical Cancer, HPV, and HPV Vaccine |

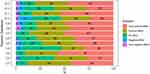

Factors Affecting Physicians’ Decisions to Recommend HPV Vaccine

The study also explored factors that would influence physicians’ decisions to recommend the HPV vaccine and found that more than 50% of the physicians were positively influenced. Reading about HPV and the vaccine, the possibility of the virus spreading in the community, and government directives to receive the vaccine were the most crucial factors influencing their decision to recommend the HPV vaccine. A positive influence of the physician’s personal reading (91%), recommendations from colleagues (88%), and government directives (87%) provided reassurance and increased confidence in recommending the vaccine to their patients. There were non-influential factors, such as advice of relatives and friends (33%) or the fact that HPV had never been declared a pandemic (41%). However, the major factor that influenced 15% of the physicians negatively was the fear of vaccine side effects (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Factors affecting the study physicians’ decision to recommend HPV vaccine. |

Physicians’ decisions to recommend the HPV vaccine are influenced by various factors, including: 1) other doctors’ recommendations; 2) advice from relatives and friends; 3) reading about HPV and the vaccine; 4) information about HPV’s non-global epidemic status; 5) HPV transmission linked to sexual activity; 6) personal beliefs about vaccines, 7) government directives, 8) the possibility of patients contracting HPV, 9) cervical cancer risk, 10) vaccine side effects, 11) the risk of viral spread, 12) fear of acupuncture use, and 13) the availability of a free vaccine. The effect of each factor was measured by a scale of 5 components ranging from very positive effect to very negative effect.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is a major public health concern worldwide, causing significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in developing countries.16 HPV is the primary causative agent of cervical cancer.17,18 Our study reveals significant insights into the knowledge and attitudes of physicians regarding cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine. Notably, the median age of physicians with good knowledge was significantly higher than those with poor knowledge. Additionally, experience played a crucial role, with 64% of physicians having more than four years of experience exhibiting good knowledge. The total median knowledge score of 38.5 indicates that while many participants responded correctly to questions about cervical cancer and HPV, misconceptions persist, particularly regarding the treatment of HPV infection, with only 38.3% accurately recognizing the lack of a cure. The data also highlight a strong relationship between knowledge and positive attitude; physicians with longer experience were 6 times more likely to have a positive attitude towards the HPV vaccine, and 5 times more likely to have a positive attitude if specialized in vaccine-related medical specialty. Despite a generally positive attitude score only 18.5% expressed a commitment to encourage vaccination among their students or daughters, reflecting a gap in support for HPV vaccination. Factors influencing the decision to recommend the HPV vaccine included reading about HPV, peer recommendations, and government directives, with over 50% of physicians positively influenced by these sources. However, concerns about vaccine side effects were a notable barrier for 15% of participants. Overall, our findings emphasize the need for targeted educational interventions that enhance better knowledge and address misconceptions, fostering a supportive environment for HPV vaccination advocacy among healthcare professionals. This is imperative, since improving better knowledge and positive attitudes regarding the disease and vaccination can lead to earlier detection of cervical cancer and increase HPV vaccination rates and thus improve health outcomes and reduce the burden on health services.19,20

Attention towards improving the awareness of physicians and their attitudes towards vaccination should be taken seriously. This is because recommendations to receive the HPV vaccine by physicians were found to be important in different studies including those conducted among non-Arabs20,21 and Arabs, either living in Arab countries or in the diaspora.22,23 The same finding applies to Saudi Arabia. For example, a recent study surveying Saudi adult females found that a recommendation from a healthcare practitioner was found to be the most influential factor in undergoing cervical cancer screening.24 Advice from healthcare providers and physicians was found to have an influence on university students25 and the Saudi public.26

Better knowledge regarding HPV and HPV vaccination was found to be a predictor of recommendations by health workers to patients to accept the HPV vaccination.27 The knowledge of Saudi Nurses was reported to be a predictor of their favorable attitudes toward the HPV vaccine.28 Although the findings from this study suggest that the participants generally had good knowledge of cervical cancer, and the HPV, vaccine, the study also highlights gaps. For example, the small number of participants who knew that there is currently no cure for HPV infection is concerning. Participants also demonstrated mixed levels of knowledge regarding HPV. Most knew about the availability of HPV testing and the transmissibility of HPV through sexual contact, yet there was poor knowledge of the asymptomatic nature of HPV infection. A previous study conducted among Saudi male medical students reported their having mediocre knowledge regarding the HPV vaccine.29 Poor knowledge was also previously found among female Saudi pharmacy and allied health sciences students in Saudi Arabia.19 This emphasizes that there is a need to revisit the medical curriculum in Saudi Arabian health colleges and the need for targeted educational interventions to address these knowledge gaps.

The study’s findings on the association between participants’ baseline characteristics and their knowledge are noteworthy. Several factors were associated with better knowledge, such as age and longer clinical experience. These results support previous studies of different groups of Saudi physicians.15,30 The results of our study provide important insights into the impact of institutional communication on individual knowledge levels regarding cervical cancer. Specifically, participants who reported being informed about cervical cancer by their institutions were three times more likely to demonstrate good knowledge of the disease. This finding underscores the significant role that institutional support for HPV and cervical cancer education plays in enhancing understanding among healthcare professionals.31 Our study also identifies substantial gaps in knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer, highlighting critical implications for both educational initiatives and public health strategies. Understanding the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer is essential, as HPV is responsible for approximately 70% of cervical cancer cases. The data further indicate that individuals with higher levels of knowledge about HPV are more likely to engage in preventive measures. This finding aligns with existing literature, which suggests that awareness of HPV’s role in cervical cancer significantly influences vaccination rates and screening practices. Therefore, targeted educational initiatives aimed at both the public and healthcare professionals are vital to bridging these knowledge gaps. Additionally, our findings reveal a strong correlation between knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer. Participants with longer years of experience had higher level of knowledge and were 5 to 6 times more likely to exhibit a positive attitude compared to those with lower knowledge levels. This suggests that enhancing knowledge not only informs but also positively influences positive attitudes, particularly in physicians with vaccine-related medical specialty. Interestingly, while nearly half of the participants (49%) reported receiving information about cervical cancer at their workplace, only 30% personally knew a woman affected by the disease. This disparity indicates that institutional awareness programs may reach a broader audience than personal connections, emphasizing the need for continued education and outreach efforts. The limited personal experience with cervical cancer among participants may contribute to a diminished sense of urgency regarding HPV and cervical cancer knowledge, potentially affecting their engagement in preventive measures. The findings are not restricted to Saudi Arabia. A study of Angolan healthcare providers showed that older providers with more clinical experience had greater knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer.32 This underscores the importance of advanced training and education in improving health-related knowledge.33,34 Several predictors of possessing better knowledge were identified in this study, such as age, medical specialty, years of experience, and being informed about cervical cancer from their institutions. The findings provide valuable insights for the development of targeted educational interventions and the implementation of HPV vaccination programs.

The analysis of attitudes found fewer significant associations. There were no significant associations between participant characteristics and attitudes. This suggests that attitudes are more complex and not easily predicted by factors such as age, experience, or specialty. It suggests that attitudes may be more influenced by personal factors, such as individual beliefs, sociocultural factors, and personal experiences.32,35,36 A notable finding was that participants who reported knowing a woman suffering from cervical cancer had more positive attitudes compared to those who did not. This suggests that personal experience of someone with cervical cancer might shape more favorable views towards prevention efforts.37,38 Concerns were noted, such as hesitancy to recommend the vaccine due to potential adverse effects and discomfort in discussing sexual education. The study found, however, that most participants agreed or strongly agreed with most of the attitude-related statements suggesting an overall positive attitude towards HPV vaccination. This is a positive finding, since favorable attitudes are essential for promoting vaccine uptake and adherence to cervical cancer screening programs.39,40 Further and more extensive investigation is recommended.

The study also explored factors that would influence physicians’ decisions to recommend the HPV vaccine and found that more than half of the study population were positively influenced and considered reading about HPV and the vaccine, the possibility of the virus spreading in the community, and government directives to receive the vaccine as the most crucial factors influencing their decision to recommend the HPV vaccine. These findings emphasize that access to scientific information from trustworthy sources such as colleagues and policy makers is essential for physicians to make informed choices.41 There appears to be a high level of public trust in the recommendations mandated by the government that enhances public trust and vaccine acceptance.42 In support of our findings, a recent study identified four primary factors influencing the decision to receive the HPV vaccine: physician recommendations, the amount of information available about the vaccine, general opinions on vaccines, and government mandates.43 However, the major factor that influenced the physicians negatively was the fear of vaccine side effects. The fear of adverse side effects associated with the HPV vaccine is a significant factor influencing vaccination rates. This fear is often fueled by misinformation and lack of understanding. A comprehensive study by Kessels et al highlights how concerns about the safety of the HPV vaccine, including potential side effects, are among the primary reasons parents and individuals choose not to vaccinate.44 A recent study has shown a significant change of opinion toward a favorable view of the HPV vaccine among physicians and the public after safety concerns were addressed.45

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw causal inferences between knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to HPV vaccines, HPV and cervical cancer. Additionally, self-reported data may introduce bias, as participants might overestimate their knowledge or attitudes. The sample may not be representative of all physicians, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the reliance on specific sources of information could overlook other influential factors that affect knowledge and attitudes. Addressing these limitations in future research will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing HPV vaccination advocacy among healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

This study provides important insights into the knowledge and attitudes of physicians and health professionals regarding cervical cancer, HPV, and the HPV vaccine. The findings highlight the need for continuous education and awareness-raising efforts to address knowledge gaps and attitudinal barriers, particularly regarding the management of HPV infection and the importance of HPV vaccination. It also emphasizes the influence of healthcare providers in promoting the HPV vaccination and emphasizes the need for comprehensive training programs to equip them with better knowledge and skills to address vaccine-related concerns and provide accurate information. Designing interventions targeting specific demographic and professional groups may be more effective in improving knowledge and promoting positive attitudes toward these critical public health issues.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee of King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh Second Health Cluster, Saudi Arabia (IRB No. 23-070 on 21.02.2023) approved the study, following the International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies.

Data Sharing Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants received an electronic survey along with information to read about the study’s ethical considerations. By agreeing to complete the survey, they electronically consented to participate voluntarily, understanding that their responses would remain confidential and that they could withdraw at any time.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Research Center at King Fahad Medical City for their valuable technical support.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R 299), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Lizano M, Berumen J, García-Carrancá A. HPV-related carcinogenesis: basic concepts, viral types and variants. Archiv Med Res. 2009;40(6):428–434. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2009.06.001

2. Sowemimo OO, Ojo OO, Fasubaa OB. Cervical cancer screening and practice in low resource countries: Nigeria as a case study. Trop J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2017;34(3):170–176. doi:10.4103/TJOG.TJOG_66_17

3. World Health Organization. Initiatives. cervical cancer elimination initiative 2024; Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-elimination-initiative.

4. Sait KH, Anfinan NM, Sait HK, Basalamah HA. Human papillomavirus prevalence and dynamics. Saudi Med J. 2024;45(3):252–260. doi:10.15537/smj.2024.45.3.20230824

5. Scott-Wittenborn N, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of HPV related malignancies. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2021;31(4):286–296. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2021.04.001

6. Anfinan N, Sait K. Indicators of survival and prognostic factors in women treated for cervical cancer at a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2020;40(1):25–35. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2020.25

7. Singh J, Baliga SS. Knowledge regarding cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2021;9:289–292. doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2020.09.012

8. Leite KRM, Pimenta R, Canavez J, et al. HPV genotype prevalence and success of vaccination to prevent cervical cancer. Acta Cytol. 2020;64(5):420–424. doi:10.1159/000506725

9. Giannone G, Giuliano AR, Bandini M, et al. HPV vaccination and HPV-related malignancies: impact, strategies and optimizations toward global immunization coverage. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;111:102467. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102467

10. Barhamain AS, Alwafi OM. Uptake of human papilloma virus vaccine and intention to vaccinate among women in Saudi Arabia. Med Sci. 2022;26(1):1. doi:10.54905/disssi/v26i123/ms189e2274

11. Markowitz LE, Drolet M, Perez N, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness by number of doses: systematic review of data from national immunization programs. Vaccine. 2018;36(32, Part A):4806–4815. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.057

12. Akkour K, Alghuson L, Benabdelkamel H, et al. Cervical cancer and human papillomavirus awareness among women in Saudi Arabia. Medicina. 2021;57(12):1373. doi:10.3390/medicina57121373

13. Almaghlouth AK, Bohamad AH, Alabbad RY, Alghanim JH, Alqattan DJ, Alkhalaf RA. Acceptance, awareness, and knowledge of human papillomavirus vaccine in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2022;14(11).

14. Alhusayn KO, Alkhenizan A, Abdulkarim A, et al. Attitude and hesitancy of human papillomavirus vaccine among Saudi parents. J Family Med Primary Care. 2022;11(6):2909–2916. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2377_21

15. Almazrou S, Saddik B, Jradi H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Saudi physicians regarding cervical cancer and the human papilloma virus vaccine. J Infection Public Health. 2020;13(4):584–590. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2019.09.002

16. Zhang X, Zeng Q, Cai W, Ruan W. Trends of cervical cancer at global, regional, and national level: data from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):894. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10907-5

17. Hull R, Mbele M, Makhafola T, et al. Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(3):2058–2074. doi:10.3892/ol.2020.11754

18. Zhang S, Xu H, Zhang L, Qiao Y. Cervical cancer: epidemiology, risk factors and screening. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32(6):720–728. doi:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.06.05

19. Easwaran V, Shorog EM, Alshahrani AA, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to cervical cancer prevention and screening among female pharmacy students at a public university in a southern region of Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2023;11(20). doi:10.3390/healthcare11202798

20. Muthukrishnan M, Loux T, Shacham E, Tiro JA, Arnold LD. Barriers to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among young adults, aged 18–35. Preventive Med Reports. 2022;29:101942. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101942

21. Flores YN, Salmerón J, Glenn BA, et al. Clinician offering is a key factor associated with HPV vaccine uptake among Mexican mothers in the USA and Mexico: a cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(3):323–332. doi:10.1007/s00038-018-1176-5

22. Ortashi O, Raheel H, Khamis J. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among male university students in the United Arab Emirates. Vaccine. 2013;31(44):5141–5144. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.016

23. Ayash C, Raad N, Finik J, et al. Arab American Mothers’ HPV vaccination knowledge and beliefs. J Community Health. 2022;47(4):716–725. doi:10.1007/s10900-022-01103-6

24. Alkhamis FH, Alabbas ZAS, Al Mulhim JE, Alabdulmohsin FF, Alshaqaqiq MH, Alali EA. Prevalence and predictive factors of cervical cancer screening in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide study. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49331. doi:10.7759/cureus.49331

25. Alshammari F, Khan KU. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions regarding human papillomavirus among university students in Hail, Saudi Arabia. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13140. doi:10.7717/peerj.13140

26. Faqeeh H, Alsulayyim R, Assiri K, et al. Perceptions, attitudes, and barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among residents in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e57646. doi:10.7759/cureus.57646

27. Btoush R, Kohler RK, Carmody DP, Hudson SV, Tsui J. Factors that influence healthcare provider recommendation of HPV vaccination. Am J Health Promotion. 2022;36(7):1152–1161. doi:10.1177/08901171221091438

28. Abdelaliem SMF, Kuaia AM, Hadadi AA, et al. Knowledge and attitudes toward human papillomavirus and vaccination: a survey among nursing students in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2023;11(12):1766. doi:10.3390/healthcare11121766

29. Farsi NJ, Baharoon AH, Jiffri AE, Marzouki HZ, Merdad MA, Merdad LA. Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among male medical students in Saudi Arabia. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(7):1968–1974. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1856597

30. Anfinan NM. Physician’s knowledge and opinions on human papillomavirus vaccination: a cross-sectional study, Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):963. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4756-z

31. Ikiroma A, Santin O, Camanda J, et al. Evaluation of human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge among healthcare professionals: a study of conference attendees in Angola. Global Public Health. 2023;18(1):2099931. doi:10.1080/17441692.2022.2099931

32. Okuhara T, Terada M, Kagawa Y, Okada H, Kiuchi T. Anticipated affect that encourages or discourages human papillomavirus vaccination: a scoping review. Vaccines. 2023;11(1). doi:10.3390/vaccines11010124

33. Swai P, Mgongo M, Leyaro BJ, et al. Knowledge on human papilloma virus and experience of getting positive results: a qualitative study among women in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. BMC Women’s Health. 2023;23(1):61. doi:10.1186/s12905-023-02192-8

34. Yoon HJ, Kim EA, Choi SI. Will humor increase the effectiveness of human papillomavirus (HPV) advertising? Exploring the role of humor, STD information, and knowledge. J Marketing Commun. 2023;29(5):491–509. doi:10.1080/13527266.2022.2048682

35. Brohman I, Blank G, Mitchell H, Dubé E, Bettinger JA. Opportunities for HPV vaccine education in school-based immunization programs in British Columbia, Canada: a qualitative study. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2024;20(1):2326779. doi:10.1080/21645515.2024.2326779

36. Dubé E, Gagnon D, Clément P, et al. Challenges and opportunities of school-based HPV vaccination in Canada. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1650–1655. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564440

37. Shariati-Sarcheshme M, Mahdizdeh M, Tehrani H, Jamali J, Vahedian-Shahroodi M. Women’s perception of barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer Pap smear screening: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2024;14(1):e072954. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072954

38. Wearn A, Shepherd L. Determinants of routine cervical screening participation in underserved women: a qualitative systematic review. Psychol Health. 2024;39(2):145–170. doi:10.1080/08870446.2022.2050230

39. Gallagher KE, LaMontagne DS, Watson-Jones D. Status of HPV vaccine introduction and barriers to country uptake. Vaccine. 2018;36(32 Pt A):4761–4767. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.003

40. Rosen BL, Shepard A, Kahn JA. US health care clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2s):S53–s65. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.10.007

41. Rosen BL, Shew ML, Zimet GD, Ding L, Mullins TLK, Kahn JA. Human papillomavirus vaccine sources of information and adolescents’ knowledge and perceptions. Global Pediatric Health. 2017;4:2333794X17743405. doi:10.1177/2333794X17743405

42. Abdelhafiz AS, Abd ElHafeez S, Khalil MA, et al. Factors influencing participation in COVID-19 clinical trials: a multi-national study. Front Med. 2021;8:608959. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.608959

43. Fallatah DI, Khalil MA, Abd ElHafeez S, et al. Factors influencing human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among parents and teachers of schoolgirls in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1403634. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1403634

44. Kessels SJM, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3546–3556. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.063

45. Maynard G, Akpan IN, Meadows RJ, et al. Evaluation of a human papillomavirus vaccination training implementation in clinical and community settings across different clinical roles. Translational Behav Med. 2024;14(4):249–256. doi:10.1093/tbm/ibae010

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.