Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 19

The Pendulum of Adherence: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Psoriasis Treatment Discontinuation

Authors Xiao Z, Jiang Y , Samah NA, Zhou H, Wang J

Received 17 March 2025

Accepted for publication 28 June 2025

Published 5 July 2025 Volume 2025:19 Pages 1893—1908

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S525490

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Zhanshuo Xiao,1,* Yilin Jiang,2,* Narina A Samah,2,* Heng Zhou,3 Junhui Wang1

1Department of Dermatology, Guanganmen Hospital, Beijing, 100053, People’s Republic of China; 2Faculty of Educational Sciences and Technology, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Johor, 81310, Malaysia; 3Student Affairs Department, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, 400016, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Yilin Jiang, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Technology, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Johor, 81310, Malaysia, Email [email protected] Junhui Wang, Department of Dermatology, Guanganmen Hospital, Beijing, 100053, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Background: Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated skin disorder requiring lifelong management, yet maintaining treatment adherence remains a significant challenge. Frequent treatment discontinuation often results in disease recurrence and poorer health outcomes, highlighting the need for a comprehensive understanding of psoriasis patients’ lived experiences concerning treatment adherence.

Methods: A phenomenological research approach was employed to explore psoriasis patients’ lived experiences concerning treatment adherence. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with 16 participants, all discontinued and later resumed treatment. Data were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to identify key themes shaping treatment adherence. Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model was also applied to elucidate the underlying mechanisms influencing treatment adherence.

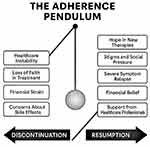

Results: Findings revealed four Group Experiential Themes (GETs) associated with treatment discontinuation: Healthcare Instability, Loss of Faith in Treatment, Financial Strain, and Concerns About Side Effects. Five GETs emerged as motivators for resuming treatment: Hope in New Therapies, Stigma and Social Pressure, Severe Symptom Relapse, Financial Relief, and Support from Healthcare Professionals.

Conclusion: This study systematically uncovers the complex factors influencing psoriasis treatment adherence. Applying phenomenology and the PPCT model illustrates the dynamic interplay between individual and environmental influences that shape psoriasis patients treatment adherence. A patient-centred, community-based, and adaptive approach is essential to bridging the gap between clinical recommendations and real-world treatment adherence, thereby improving long-term disease management and enhancing psoriasis patients’ quality of life.

Keywords: psoriasis, lived experience, treatment adherence, interpretative phenomenological analysis, PPCT model, treatment discontinuation, patient-centered

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, systemic, immune-mediated condition with a diverse clinical spectrum, affecting approximately 2–3% of the global population.1 Effective management often requires lifelong treatment adherence, with treatment outcomes largely dependent on a patient’s ability to follow medical recommendations and adapt therapeutic strategies as needed.2

However, treatment adherence is challenged by multiple factors, and the reasons behind treatment discontinuation are complex, making them difficult to capture through rigid quantitative research methods.3,4 To address this gap, this study adopts a phenomenological approach, integrating Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model to explore the lived experiences of psoriasis patients (PP) regarding treatment discontinuation and resumption.5,6

Specifically, this research seeks to answer two key questions:

What are the reasons for treatment discontinuation among PP?

What factors motivate PP who have discontinued treatment to resume therapy?

By capturing the lived experiences of PP, this study provides deeper insights into the psychological, social, and systemic factors influencing treatment adherence. The findings aim to inform more patient-centred management strategies, ultimately bridging the gap between clinical recommendations and real-world treatment adherence.

Psoriasis: Clinical Features and Rising Global Prevalence

Psoriasis is a common, chronic papulosquamous skin disease with a global distribution, affecting individuals of all ages and imposing a substantial burden on both patients and society.7 Clinically, it is characterized by erythematous plaques covered with silvery scales, particularly over the extensor surfaces, scalp, and lumbosacral region.8 In severe cases, psoriasis extends beyond cutaneous manifestations, leading to systemic complications such as psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome.7,8 Moreover, the pathogenesis of psoriasis is influenced by genetic susceptibility, particularly in individuals carrying the HLA-Cw6 risk allele, though non-genetic factors also play a crucial role in disease onset and recurrence.9,10 Key exacerbating factors include infections, dysbiosis of skin and gut microbiota, dysregulated lipid metabolism, hormonal imbalances, and mental health disorders.10,11 Additionally, environmental triggers such as skin trauma (Koebner phenomenon), unhealthy lifestyles, and medication use can further induce or worsen psoriasis.7,10 These intricate interactions between genetic, immunological, and environmental factors make a complete cure for psoriasis fundamentally challenging.

The global incidence of psoriasis is increasing, with estimates indicating that over 125 million individuals are affected worldwide. While the prevalence varies across regions, it continues to rise annually.12 These regional differences may be attributed to genetic predisposition (eg, HLA-Cw6 distribution), environmental factors (eg, climate, infections, smoking, and obesity), and differences in healthcare infrastructure and diagnostic capabilities.7,10,13 Additionally, rapid industrialization, lifestyle changes, and high-stress living conditions, along with poor dietary habits and the widespread adoption of advanced diagnostic techniques, have contributed to the rising global burden of psoriasis, particularly in highly urbanized areas.10,14,15 Overall, psoriasis has seen a sharp increase in prevalence in recent years, reflecting the complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and societal factors driving this trend.

Challenges in Psoriasis Treatment: Complex Aetiology and Therapeutic Barriers

The primary challenge in treating psoriasis lies in its complex aetiology, which involves a multifaceted interplay of genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and environmental triggers.7,10,12 This complexity makes the disease prone to recurrence and difficult to cure. At the genetic level, studies have demonstrated a strong association between psoriasis and multiple susceptibility loci, such as HLA-C*06:02, which may contribute to disease development by excessively activating the immune system.16,17 In terms of immune dysregulation, the abnormal activation of the IL-23/Th17 axis is considered a key pathological mechanism in psoriasis, leading to excessive proliferation of keratinocytes and the overproduction of inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-17, IL-22, and TNF-α), ultimately resulting in skin inflammation and tissue damage.18 Additionally, environmental factors—including streptococcal infections, psychological stress, and certain medications (such as β-blockers or lithium salts)—can trigger or exacerbate the disease, further complicating its management.10,19

Furthermore, despite the availability of diverse treatment options, including topical therapies (eg, glucocorticoids, vitamin D3 analogues), phototherapy (eg, narrow-band ultraviolet B), and systemic therapies (eg, biologics, traditional immunosuppressants), significant challenges remain.8 First, long-term treatment adherence is necessary, yet many PP struggle to maintain a standardized regimen due to individual variability in treatment efficacy or tolerance issues.20 Second, while systemic therapies such as biologics provide effective treatment for moderate to severe cases, their high cost often presents a financial barrier to sustained therapy.21 Furthermore, potential side effects of medications—such as an increased risk of infection with immunosuppressants and the development of drug resistance with biologics—limit their long-term feasibility.22 These factors collectively contribute to frequent treatment interruptions due to financial burden, unstable efficacy, or adverse effects, ultimately leading to disease fluctuations or exacerbations and further complicating disease management.

Bridging the Gap: Understanding PP Treatment Adherence Through Lived Experiences

According to consensus guidelines from multiple authoritative handbooks, the effectiveness of psoriasis treatment and chronic disease management is closely linked to sustained and standardized therapy.7,23 Such an approach not only effectively controls lesion size and disease severity but also reduces the risk of comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.7,24 However, in real-world clinical practice, PP often struggle to adhere to long-term treatment due to a variety of complex factors, leading to disease recurrence and exacerbation, which can further increase treatment difficulty.20,25 Therefore, an in-depth exploration of the key factors influencing treatment adherence, including the reasons for treatment discontinuation and the driving mechanisms of re-treatment behaviours, is of significant importance for optimizing long-term PP management strategies.26 Further research on these mechanisms will enhance PP adherence, support patient-centred treatment, and provide a scientific basis for patient-based interventions, ultimately improving PP’s quality of life.

To gain a deeper understanding of the factors influencing treatment adherence in PP and the underlying mechanisms, phenomenology provides an optimal research perspective.6 This approach emphasizes individuals’ lived experiences, focusing on how PP perceive and interpret their condition and treatment journey, rather than relying solely on objective medical indicators or external behavioural patterns.27 Moreover, unlike quantitative research, which primarily infers influencing factors through statistical analysis, phenomenology recognizes PP as holistic individuals with complex lives and subjective experiences, rather than merely viewing them as clinical cases.3 By capturing the cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions of treatment decision-making, phenomenological research uncovers the dynamic interactions that shape treatment adherence.28 This approach not only enables stakeholders to gain deeper insights into PP’s needs and challenges but also provides practical guidance for developing more targeted intervention strategies. Ultimately, integrating phenomenological insights into psoriasis management can enhance patient-centred care, improve long-term treatment adherence, and contribute to better overall quality of life for individuals living with psoriasis.29,30

The Process-Person-Context-Time Model

When examining the lived experiences of PP, both external factors—such as healthcare accessibility, social support, and environmental stressors—and internal motivations, including personal beliefs, psychological resilience, and perceived treatment efficacy, play a crucial role in shaping treatment adherence.22,25,26 Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model provides a structured framework to explore how PP navigate their treatment journeys, emphasizing the dynamic interactions between individual, social, and systemic influences in long-term disease management.5

As an extension of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, the PPCT model highlights the interconnected and evolving nature of human experiences.31 The process component focuses on the reciprocal interactions between individuals and their environment that shape behaviours over time.32 The person dimension accounts for individual characteristics, such as psychological traits, genetic predisposition, and personal history, which influence decision-making.33 The context encompasses the broader social and environmental structures that shape experiences, including family, healthcare access, and societal attitudes.5 Lastly, the time element highlights how these interactions evolve across different life stages and external circumstances, reinforcing the need for a longitudinal perspective in understanding treatment adherence.5,31 By applying the PPCT model, researchers can holistically analyze PP lived experience, recognizing that treatment adherence is not solely an individual decision but rather an outcome of complex and dynamic interactions.

Methodology

Research Design

This study employed a phenomenological research approach to explore the lived experiences of PP regarding treatment adherence. Phenomenology was selected for its ability to provide an in-depth understanding of how individuals perceive and interpret their condition and treatment journey, capturing the subjective and contextual factors influencing treatment adherence.6 To ensure methodological rigor and transparency, the study was conducted in accordance with the qualitative research guidelines published by EQUATOR (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research), adhering to established best practices in qualitative health research.34

Study Population and Sampling

This study was conducted in the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary public hospital in Beijing, China. The hospital is a leading medical center in the region, providing specialized care for chronic dermatological conditions such as moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Participants were recruited through collaboration with board-certified dermatologists working in the department, who played an active role in the identification and referral process. Eligible participants were those who had previously discontinued and later resumed treatment at least once in their disease management history, as confirmed through medical records and clinical interviews (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic Variables of the Psoriasis Patients |

During routine outpatient consultations, dermatologists introduced the study to potential participants and referred those expressing interest to the research team. The research team then provided a comprehensive explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, and ethical considerations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. All participants consented to the use of their anonymized responses and direct quotations in the final publication. A purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure a diverse representation of lived experiences, with variation in age, gender, socioeconomic status, disease duration, and treatment history. The final sample consisted of 16 participants, aligning with recommended sample sizes for Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), thus enabling both idiographic depth and cross-case thematic analysis.6

Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews, designed to elicit rich narratives of PP’ s lived experiences with treatment adherence. The interview guide was initially developed by the research team and subsequently refined based on feedback from two psychologists with expertise in qualitative methods. Key interview topics included: (1) reasons for treatment discontinuation, (2) motivations for resuming treatment, (3) the influence of social and emotional factors on treatment adherence decisions, and (4) personal coping strategies in managing long-term psoriasis care.

Interviews were conducted either in person at the hospital or via secure online platforms (eg, Tencent Meeting), depending on participants’ preferences and logistical constraints. Each session lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes and was audio-recorded with informed consent. Field notes were also taken during and after the interviews to document non-verbal cues, emotional expressions, and contextual observations that could enrich the interpretive analysis.

Interviews continued until data saturation was achieved—defined as the point at which no new valuable contents emerged and both the researchers and participants felt that the existing content sufficiently captured the range and depth of PP’s lived experiences.3

Data Analysis

This study primarily employed an IPA approach for data analysis.6 The process consisted of the following steps:

Step 1: Immersion in the First Case – Reading and Re-Reading

The initial step in IPA involved deep engagement with the original data. Although audio recordings had been transcribed verbatim, the researcher revisited the recordings while cross-referencing them with the transcripts. This process ensured that the participant remained central to the analysis. Given that individuals are often accustomed to rapidly summarizing complex information, this stage encouraged a deliberate slowing down, counteracting the tendency for hasty synthesis.

Step 2: Exploratory Noting

At this stage, a detailed examination of semantic content and language use was conducted. The researcher adopted an open and reflective approach, noting any aspects of interest within the transcript. This process fostered an increasing familiarity with the data while also identifying specific ways in which participants articulated, conceptualized, and interpreted their experiences. The text was divided into meaning units, with each unit assigned a corresponding analytical comment.

Step 3: Constructing Experiential Statements

In this step, the researcher transitioned from working primarily with the transcript to focusing on the exploratory notes. The goal was to condense the data while preserving its depth and complexity. This involved synthesizing the most salient aspects of the exploratory notes into experiential statements, which captured key features of the participant’s account while remaining closely tied to the original transcript.

Step 4: Identifying Connections Across Experiential Statements

This phase involved mapping relationships among experiential statements to explore their interconnections. Each statement was treated with equal importance, allowing for the emergence of patterns without imposing preconceived hierarchies.

Step 5: Naming Personal Experiential Themes (PETs) and Organizing Them in a Table

Clusters of related experiential statements were assigned descriptive titles, forming PETs that characterized each participant’s unique experiences. These themes were systematically organized into a table for further analysis.

Step 6: Conducting Individual Analysis of Additional Cases

The process was then repeated for subsequent participants. Each case was analyzed independently to honour its distinctiveness and to ensure that individual experiences were interpreted on their own terms before cross-case comparisons were made.

Step 7: Developing Group Experiential Themes (GETs) Across Cases

The final stage involved identifying GETs by examining patterns of convergence and divergence across the PETs generated in the previous step. Rather than establishing a generalized or normative representation of the experience, this step aimed to highlight both shared and unique elements of participants’ accounts. The focus remained on capturing the depth and variability of lived experiences rather than constructing an ‘average’ experience.

To facilitate data coding and organization, N-Vivo software was utilized. To ensure rigor and trustworthiness, multiple validation strategies were employed, including peer debriefing, researcher reflexivity, and triangulation through cross-referencing with medical records where applicable.3,35 These methodological measures strengthened the credibility and reliability of the findings, ensuring a comprehensive and accurate representation of PP’s lived experiences.

The coding and analysis team primarily consisted of researchers from mainland China, ensuring cultural sensitivity in the study.3,36 The team included a dermatology dermatologist with a medical doctorate (A) and two psychologists with qualitative psychology training (B and C). The transcription process was primarily conducted by A, ensuring the accuracy of medical terminology. The IPA was led by B, who had no prior dermatology background, aligning with the phenomenological principle of “epoché” to minimize preconceptions.6 After completing the analysis, all three researchers collaboratively reviewed and refined the final results through discussion and revision.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant institutional review board (IRB), and the study was conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2024–177-KY-01). PP provided informed consent after receiving detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and confidentiality measures. PP were entirely voluntary, with individuals retaining the right to withdraw at any time. To ensure anonymity and data security, pseudonyms were used, and all data were securely stored and encrypted.

Result

Following a rigorous analysis in accordance with the methodological framework, both research questions have been systematically addressed. For Research Question 1, four GETs were identified: Healthcare Instability, Loss of Faith in Treatment, Financial Strain, and Concerns About Side Effects. These themes encapsulate the primary factors contributing to treatment discontinuation among PP. For Research Question 2, five GETs were identified: Hope in New Therapies, Stigma and Social Pressure, Severe Symptom Relapse, Financial Relief, and Support from Healthcare Professionals. These themes highlight the key motivators that influence PP’s decisions to resume treatment, as shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The adherence pendulum: factors influencing psoriasis treatment behaviours. |

The conceptual metaphor of a pendulum—used in the figure—symbolizes the dynamic and recurrent movement between discontinuation and resumption that characterizes PP’s treatment journeys. Just as a pendulum swings in response to opposing forces, patients’ treatment adherence are shaped by shifting psychological, social, and contextual pressures over time. Rather than representing a linear decision-making process, the pendulum illustrates the continuous, back-and-forth negotiation between disengagement and re-engagement with treatment. This metaphor underscores the fluctuating nature of treatment adherence and highlights the need for interventions that are both flexible and responsive to the evolving lived realities of patients.

What are the Reasons for Treatment Discontinuation Among PP?

GET 1: Healthcare Instability

After studying abroad, I was unable to continue my treatment because I did not trust the local doctors’ protocols. (P5-PET12)

Due to a work transfer, I moved to a place with a better climate, which reduced my itching, so I stopped taking my medication. (P10-PET1)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I was unable to visit the hospital for prescriptions, and eventually, I just stopped treatment, occasionally applying some topical medication. (P2-PET2)

I used traditional Chinese medicine, but the daily process of decocting herbs was too troublesome. (P14-PET1)

After a work transfer, I went to a new hospital where they gave me hormone injections. At first, it worked well, but later, my condition worsened significantly. (P9-PET2)

I had been receiving traditional Chinese medicine treatment and had recommended it to many friends, but in the end, I could no longer secure an appointment. (P7-PET10)

I underwent phototherapy for a while, and it was somewhat effective, but I got too busy with work and stopped. (P6-PET8)

GET 2: Loss of Faith in Treatment

The results were almost the same whether I received treatment or not, so I only went when I had time. (P2-PET2)

I had hormone injections for a while, but the effects rebounded, so I gave up. (P1-PET7)

If I did not get the injections, my symptoms worsened. I had to get injections every week, which was too troublesome. (P4-PET6)

No matter how I treated it, it kept recurring, and I lost patience. (P14-PET3)

The injections stopped working, so I just gave up on treatment. (P7-PET3)

I took a lot of medication, but the high humidity in my hometown triggered relapses, so I stopped. (P6-PET3)

I took Chinese medicine, which improved my appetite and sleep, but my psoriasis did not get better. (P11-PET2)

GET 3: Financial Strain

Because of the pandemic, I lost my income as a truck driver. (P13-PET1)

The price of certain injections was too high, and since the treatment did not work anyway, I stopped. (P2-PET4)

It was not getting better, and I could not afford it anymore, so I gave up. (P6-PET8)

GET 4: Concerns About Side Effects

I stopped treatment because I was trying to conceive and was worried about the potential effects on the fetus. (P14-PET3)

During treatment, I had unpredictable gastrointestinal reactions, which kept me running to the bathroom all the time. (P9-PET3)

The medication made my stomach feel very uncomfortable When my symptoms eased in the summer, I stopped taking it. (P7-PET1)

The medication made my mouth extremely dry. I worried that if I continued, my liver would suffer severe damage. (P6-PET5)

After a period of hormone injections, I gained a lot of weight, so I stopped. (P3-PET5)

I suddenly developed heart failure, and the hospital told me to stop the biologic treatment during that time. (P2-PET2)

What Factors Motivate Psoriasis Patients Who Have Discontinued Treatment to Resume Therapy?

GET 1: Hope in New Therapies

After finishing breastfeeding, I learned that I could receive biologic injections, so I resumed treatment. (P6-PET5)

I once lost my job and self-confidence because of psoriasis. I locked myself at home and avoided social interactions. One day, I saw a news report about a new oral targeted therapy, and it felt like a ray of hope in the darkness. (P7-PET1)

A neighbor in my community had been receiving injections for six months without a relapse, so I decided to try it too. (P16-PET6)

GET 2: Stigma and Social Pressure

In summer, my symptoms worsened, and when I wore short sleeves, my friends kept asking about it. I had to keep explaining that it was not contagious. (P2-PET5)

While traveling, I had to share a room with a colleague, and I was afraid of exposing any part of my body. (P1-PET2)

When eating, my hair kept falling into my bowl, and no one wanted to sit with me. (P5-PET5)

GET 3: Financial Relief

Some medications were included in the national health insurance program. (P3-PET4)

Based on recommendations from fellow patients, I decided to try biologics, as they became more affordable. (P13-PET4)

Previously, biologic treatments were not covered by insurance, but once they were included, I started using them. (P12-PET1)

GET 4: Severe Symptom Relapse

When I returned home and changed my pajamas, I saw that the floor was covered with my skin flakes. (P4-PET11)

In winter, my condition relapsed, and my face became covered in psoriasis patches. (P15-PET2)

As winter worsened my symptoms, I resumed injections. (P14-PET2)

I did not want to explain to others anymore, so I just told people it was an allergy.(P8-PET1)

As a truck driver, the itching was so severe that it affected my ability to drive safely. (P2-PET7)

GET 5: Support from Healthcare Professionals

I really liked my doctor, and my doctor really liked me, so I kept going back to them. (P3-PET3)

My doctor told me that this was the best option available and encouraged me to stay committed and see how it worked. (P7-PET5)

A specialist came to my local community hospital and recommended biologics to me. (P15-PET3)

Discussion

In the discussion section, the factors contributing to treatment discontinuation or abandonment, as identified in Research Question 1, are thoroughly analyzed using the PPCT model, exploring the interactions between individual, social, and systemic influences on adherence. Meanwhile, the findings from Research Question 2 are incorporated into the recommendations part, providing targeted strategies to improve treatment adherence and ensuring that the insights gained translate into practical, patient-centred interventions.

Healthcare Instability

At process level, the accounts illustrate how changes in healthcare environments disrupt treatment processes. PP who relocated or experienced shifts in healthcare systems (eg, moving abroad or changing hospitals) struggled with trust in new medical protocols. The hesitation to continue treatment under an unfamiliar doctor underscores how disruptions in patient-provider relationships and inconsistencies in treatment recommendations affect adherence.37 Similarly, the reliance on herbal remedies and light therapy suggests an ongoing process of trial-and-error in treatment selection, where ease of access and perceived effectiveness influence decisions.

At person level, PP’s beliefs about treatment effectiveness play a crucial role in decision-making. Moreover, some PP stopped medication due to environmental changes, such as moving to a climate that alleviated symptoms, suggesting that perceptions of disease severity can dictate treatment adherence.38 Additionally, the switch to herbal medicine and light therapy reflects a preference for alternative treatments, although convenience and feasibility (eg, the difficulty of decocting Chinese medicine or managing work schedules) ultimately shaped adherence.39

At context level, the broader healthcare system significantly impacted treatment continuity. PP faced barriers such as limited access to trusted doctors, hospital overcrowding, and systemic disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic.40 These limitations prevented regular follow-ups, timely prescriptions, and consistent medical guidance, leading some PP to abandon treatment or rely on self-management strategies (eg, occasional topical application).7,10 The difficulty of securing appointments, particularly for traditional Chinese medicine doctors, further highlights disparities in healthcare accessibility, which disproportionately affect those seeking specialized treatments.

At the time level, treatment decisions evolved over time, influenced by life transitions such as job transfers, increased work responsibilities, and public health crises. For example, PP who initially found success with hormone injections or light therapy later abandoned these treatments due to worsening side effects or work constraints. This reflects how treatment adherence is not static but rather fluctuates based on changing life circumstances.38 The long-term impact of inconsistent treatment access may contribute to disease progression, reinforcing the need for stable, patient-centred care solutions.

Loss of Faith in Treatment

At the process level, the perceived inefficacy of treatment is a key driver of discontinuation. Many PP observed no significant improvement whether they continued or discontinued therapy, leading to frustration and disengagement. The experience of treatment failure or diminishing effects over time (eg, rebound effects from hormone therapy) further reinforced the belief that continued treatment was futile.11,12 PP also cited inconvenience and burdensome treatment regimens, such as weekly injections or taking large amounts of medication, as reasons for stopping therapy. These patterns highlight how negative treatment experiences and unmet expectations reduce motivation for adherence.41

At person level, psoriasis is a chronic and recurring condition, and many PP expressed frustration and loss of patience when treatments failed to deliver sustained improvements. The belief that the disease will always return, regardless of treatment, contributed to treatment fatigue—a psychological state where continuous effort without rewarding outcomes leads to disengagement. Some PP valued secondary benefits of treatment, such as improved sleep and appetite from Chinese medicine, but ultimately discontinued therapy due to lack of dermatological improvement. These findings suggest that PP’s psychological resilience and expectations influence their ability to persist with long-term treatment plans.39,41

At the context level, external conditions play a significant role in treatment discontinuation. Some PP discontinue treatment due to environmental factors, such as high humidity in their hometown, which they perceive as contributing to relapses, leading to the belief that treatment is ineffective regardless of adherence. Others cite practical difficulties, including the inconvenience of frequent injections or the burden of taking large quantities of medication. These contextual factors highlight the interplay between treatment accessibility, lifestyle compatibility, and environmental influences, all of which shape patient decision-making and contribute to the challenges of maintaining long-term adherence.26,38

At the time level, as PP progress through different stages of their disease, their perspectives on treatment evolve. Some initially pursued aggressive treatment regimens, only to become disillusioned when results did not meet their expectations. Others experimented with different treatment approaches, such as hormone therapy, Chinese medicine, but ultimately abandoned them due to long-term ineffectiveness. This pattern suggests that early optimism often gives way to skepticism and eventual disengagement when treatment fails to deliver sustained relief.41 The long-term nature of psoriasis and recurring relapses further reinforce the belief that treatment is not worthwhile, leading PP to deprioritize medical intervention.

Financial Strain

At process level, for many PP, treatment discontinuation was directly linked to high costs and lack of financial stability. The inability to afford medications or injections, especially when the treatment was perceived as ineffective, reinforced the belief that continuing therapy was futile. Some PP experienced income loss due to external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which further restricted access to healthcare.12,40 These financial constraints disrupted the continuity of care, forcing patients to prioritize essential expenses over long-term treatment.

At person level, the emotional burden of investing in expensive treatments without seeing long-term improvements led to frustration, resignation, and eventual disengagement. Many PP expressed a sense of hopelessness, feeling that their condition was incurable and therefore not worth further financial sacrifice. The intersection of economic stress and chronic illness contributed to a state of learned helplessness, where patients no longer believed treatment could provide meaningful relief.42

At the context level, the high cost of psoriasis treatments, particularly injections and specialty medications, reflects broader systemic healthcare disparities. Many PP do not have adequate insurance coverage or access to affordable treatment alternatives, leading to out-of-pocket expenses that are unsustainable over time. Furthermore, job-related instability—such as being a lorry driver with no financial security during the pandemic—exacerbates healthcare inequities, disproportionately affecting PP in low-income or unstable employment situations.26,39

At the time level, psoriasis is a lifelong condition, and financial strain is not a one-time obstacle but rather a persistent challenge that influences treatment decisions over time. PP may initially attempt to manage costs but ultimately discontinue treatment once financial resources are depleted. This highlights the long-term vulnerability of individuals with chronic conditions who lack stable financial support. Over time, the repeated experience of unaffordable treatments may discourage PP from even considering future therapies, reinforcing chronic disengagement from medical care.4

Concerns About Side Effects

At the process level, the decision to stop psoriasis treatment is often a result of persistent or severe side effects that disrupt daily life. PP in this study reported gastrointestinal discomfort, excessive dryness, weight gain, and concerns about liver damage as key reasons for discontinuation. Some PP stopped treatment as soon as symptoms improved, suggesting that temporary relief reduces motivation to endure unpleasant side effects. Others had serious medical complications, such as heart failure, leading to physician-directed discontinuation of biologic treatments. These experiences highlight how unmanageable or unexpected side effects weaken long-term treatment adherence to therapy.43

At the person level, personal beliefs and perceived risk strongly influence treatment decisions. Some PP discontinued medication due to fears of long-term organ damage, particularly concerning liver function and hormonal side effects. The desire to conceive led others to stop treatment proactively, fearing potential harm to the fetus. These decisions demonstrate how individual health priorities shift based on life circumstances, with PP weighing short-term symptom relief against potential long-term harm.43,44

At the context level, external factors, including medical advice, healthcare accessibility, and information availability, shape PP’s understanding of medication risks. While some PP stopped treatment under direct physician guidance, others relied on self-assessment of side effects without professional consultation. This suggests that PP may lack sufficient medical support in managing side effects, leading to premature discontinuation. Additionally, the availability of alternative treatment options (eg, stopping medication when symptoms subside in summer) further influences decision-making, showing that seasonal patterns and perceived disease severity affect adherence.45

At the time level, side effects are not static; PP’s experiences and tolerance levels change over time. Some initially endured symptoms but later discontinued treatment when discomfort persisted or worsened. Others faced life-stage-related decisions, such as pregnancy planning, prompting them to reassess risks and discontinue medication. This illustrates how treatment adherence fluctuates based on changing health conditions, life priorities, and cumulative side effect experiences.38,46

The Recommendation

In Research Question 2, the emerging themes—Hope in New Therapies, Stigma and Social Pressure, Severe Symptom Relapse, Financial Relief, and Support from Healthcare Professionals—are identified as key positive factors that encourage PP to resume formal treatment. Therefore, this section integrates these experiences and, based on the PPCT model, proposes strategies to enhance treatment adherence among PP, as shown in Figure 2. However, it is important to note that, due to the nature of qualitative research, these recommendations are not intended to be universally applicable at this stage.3

|

Figure 2 The strategies to enhance treatment adherence among psoriasis patients. |

At the level of Process, improving treatment continuity requires addressing the frequent disruptions caused by relocation, inconsistent medical advice, and accessibility issues. Many PP struggle with trust in new healthcare providers, leading to treatment discontinuation when they move or change hospitals.

To mitigate this, a digitally integrated healthcare system should be established, allowing patient records and treatment histories to be seamlessly shared across facilities. Tele-medicine consultations should also be expanded to help PP maintain continuity with their preferred healthcare providers, even after relocating.47 Additionally, simplifying treatment regimens—such as offering long-acting biologics or alternative formulations of Chinese medicine—can reduce the burden of daily treatment maintenance. Furthermore, ensuring that healthcare professionals adhere to standardized treatment guidelines—including both mainstream and alternative therapies—across different hospitals and regions can help eliminate inconsistencies in care, thereby reducing PP distrust in new treatment protocols and improving overall treatment adherence. Moreover, greater efforts should be made to engage relevant specialists in more community-based healthcare initiatives, strengthening the linkages between hospitals, community clinics, schools, and families.48 By fostering collaborative partnerships between these institutions, high-quality medical resources can be made more accessible to a broader range of PP, particularly those in underserved areas. By focusing on process-level improvements, PP can receive stable, uninterrupted care, reducing the likelihood of abandonment due to logistical and systemic challenges.

At the level of Person, treatment adherence is influenced by PP’s psychological responses, expectations, and personal priorities. Many PP develop treatment fatigue after experiencing repeated relapses or lack of sustained improvement, leading to frustration and eventual disengagement. Others stop treatment due to side effects, concerns about long-term organ damage, or lifestyle constraints that make treatment adherence difficult.

To address these personal barriers, psychosocial support programs should be integrated into psoriasis management, helping PP cope with the emotional burden of chronic disease.49 Moreover, shared decision-making between PP and doctors should also be encouraged, allowing PP to tailor their treatment plans based on their personal values, work schedules, and side effect tolerance.50 Additionally, cognitive-behavioural orientation interventions could help PP reframe their understanding of chronic illness, emphasizing long-term disease control rather than an unrealistic expectation of a cure.51

At the level of Context, systemic barriers—including financial constraints, healthcare accessibility, and social determinants of health—must be addressed to improve psoriasis treatment adherence. Many patients discontinue therapy due to high treatment costs, lack of insurance coverage, or job-related instability that prevents them from affording necessary medications.

Expanding insurance coverage and financial assistance programs can help mitigate these issues, ensuring that PP do not have to choose between basic necessities and medical care.52 Governments and healthcare organizations should also work to increase the availability of affordable treatment options, such as biosimilars or generic medications, while improving access to specialized care in both urban and rural settings. Additionally, cultural beliefs and social stigma surrounding psoriasis may prevent some PP from seeking consistent treatment, emphasizing the need for public awareness campaigns and workplace accommodations to support PP managing the disease.53 By improving contextual factors such as affordability, accessibility, and societal support, healthcare systems can create a more equitable environment where all PP have access to sustained, high-quality treatment.

At the level of Time, it is essential to recognize that treatment needs and priorities evolve throughout a PP’s life, influencing their willingness and ability to adhere to therapy. PP who initially commit to aggressive treatment regimens may later deprioritize therapy due to job relocations, pregnancy, financial instability, or shifting health concerns. Others may temporarily abandon treatment after experiencing symptom relief, only to resume when symptoms worsen.

To accommodate these fluctuations, psoriasis management strategies should be designed with built-in flexibility, allowing PP to adjust their treatment plans as their life circumstances change.54 Moreover, personalized treatment timelines should be developed, where PP have the option to transition between different levels of therapy rather than completely discontinuing treatment.55 Additionally, long-term follow-up programs should be implemented to check in with patients even after they discontinue treatment, encouraging re-engagement when PP are ready.56 Furthermore, digital health tools, such as trustworthy AI-powered systems for symptom tracking and medication reminders, can support PP in maintaining adherence to their treatment plans over time.57 By acknowledging the long-term nature of psoriasis and allowing for adaptable treatment approaches, healthcare providers can ensure that PP receive continuous support, even as their priorities shift.

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small (n=16), which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Although efforts were made to include participants with diverse demographic and clinical backgrounds, the study may not fully capture the full spectrum of experiences among PP, particularly those in rural areas or with limited healthcare access. Future research with a larger, more representative sample could provide a broader understanding of treatment adherence patterns.

Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential recall bias. PP were asked to reflect on past decisions regarding treatment discontinuation and resumption, which may be influenced by memory distortions or personal interpretations. While phenomenological research values lived experiences, future studies could incorporate objective medical records or longitudinal tracking to validate self-reported treatment behaviours.

Finally, the study focused primarily on PP experiences and perspectives, without direct input from healthcare providers. While this approach provided deep insight into the lived experiences of PP, a more comprehensive analysis could benefit from integrating the perspectives of dermatologists, psychologists, and healthcare policymakers to understand systemic barriers and potential interventions more holistically.

Conclusion

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic disease influenced by a combination of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors. Its rising global prevalence and significant impact on physical, psychological, and social well-being highlight the urgent need for improved disease management strategies.7,8 Despite advancements in therapeutic options, treatment adherence remains a critical challenge due to medical resource disparities, dissatisfaction with treatment outcomes, financial constraints, and concerns about side effects.11,15,38 Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach that incorporates patient-centred care, systemic healthcare improvements, and ongoing support mechanisms.

By adopting a phenomenological research approach, this study has provided valuable insights into the lived experiences of PP, particularly the factors influencing treatment discontinuation and resumption. Through a rigorous methodological analysis, both research questions have been systematically addressed. For Research Question 1, four GETs emerged: Healthcare Instability, Loss of Faith in Treatment, Financial Strain, and Concerns About Side Effects. These themes encapsulate the primary factors contributing to treatment discontinuation, illustrating how systemic barriers, psychological distress, and financial difficulties undermine long-term adherence. For Research Question 2, five GETs were identified: Hope in New Therapies, Stigma and Social Pressure, Severe Symptom Relapse, Financial Relief, and Support from Healthcare Professionals. These themes highlight the key motivators that drive patients to resume treatment, emphasizing the role of medical advancements, social dynamics, symptom severity, and financial accessibility in re-engagement with therapy. The application of Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT model provides a structured framework for understanding the dynamic interactions shaping patient decision-making.

By applying the PPCT model, this study highlights the multifaceted challenges influencing psoriasis treatment adherence and underscores the importance of a patient-centered, adaptable approach to disease management. At the process level, improving treatment continuity through digitally integrated healthcare systems, telemedicine expansion, and standardized treatment protocols can help mitigate disruptions caused by relocation and inconsistent medical guidance. At the person level, addressing treatment fatigue, psychological distress, and personal lifestyle constraints through psychosocial support, shared decision-making, and community-based treatment adherence strategies can enhance long-term engagement. At the context level, systemic barriers—such as financial strain, healthcare inaccessibility, and social stigma—must be addressed through expanded insurance coverage, financial assistance programs, and public awareness initiatives to create an equitable treatment environment. Finally, at the time level, recognizing that treatment needs and priorities evolve over a PP’s lifetime necessitates flexible, personalized treatment plans, long-term follow-up programs, and digital health interventions to support ongoing care. By integrating these process, person, context, and time-based interventions, healthcare systems can establish a more sustainable, accessible, and individualized approach to psoriasis management, ultimately enhancing PP adherence, improving treatment outcomes, and elevating overall quality of life.

Ultimately, bridging the gap between clinical recommendations and real-world PP experiences necessitates a holistic, patient-centered, and interdisciplinary approach to psoriasis management. Future research should further investigate the interplay between psychological resilience, healthcare accessibility, and patient-provider relationships, recognizing their collective impact on treatment adherence. By fostering a deeper understanding of patient lived experiences and systematically addressing the key barriers to sustained therapy, healthcare practitioners can develop more effective, flexible, and personalized disease management strategies. This, in turn, will lead to improved patient well-being, enhanced quality of life, and better long-term disease control, ensuring that psoriasis treatment aligns with both medical best practices and the realities of patient care.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No.: 2024-177-Ky-01).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (ZZ13-YQ-021) and the High-Level Chinese Medical Hospital Promotion Project (No. HLCMHPP2023027) and The Escort Project of Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medicine Science-Backbone Talent Cultivation Project (No. GAMHH9324021) and Science and Technology Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Grant No. CI2021A02314). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Disclosure

Zhanshuo Xiao and Yilin Jiang and Narina A.Samah are co-first authors for this study. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

2. Zaghloul SS, Goodfield MJD. Objective assessment of compliance with psoriasis treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(4). doi:10.1001/archderm.140.4.408

3. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches; 2017. Available from: https://openlibrary.org/books/OL28633749M/Qualitative_Inquiry_and_Research_Design.

4. Avazeh Y, Rezaei S, Bastani P, Mehralian G. Health literacy and medication adherence in psoriasis patients: a survey in Iran. BMC Primary Care. 2022;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12875-022-01719-6

5. Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental ecology through space and time: a future perspective. In: American Psychological Association eBooks; 2004:619–647. doi:10.1037/10176-018

6. Smith JA, Larkin M, Flowers P. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. 2nd Ed. Sage Publications; 2021. https://www.torrossa.com/it/resources/an/5282221.

7. Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):263–271. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61128-3

8. Raharja A, Mahil SK, Barker JN. Psoriasis: a brief overview. Clin Med. 2021;21(3):170–173. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2021-0257

9. Boehncke W, Boehncke S, Schon MP. Managing comorbid disease in patients with psoriasis. BMJ. 2010;340(jan15 1):b5666. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5666

10. Liu S, He M, Jiang J, et al. Triggers for the onset and recurrence of psoriasis: a review and update. Cell Commun Signaling. 2024;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01381-0

11. Gupta S, Syrimi Z, Hughes DM, Zhao SS. Comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(2):275–284. doi:10.1007/s00296-020-04775-2

12. Zhang Y, Dong S, Ma Y, Mou Y. Burden of psoriasis in young adults worldwide from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1308822

13. Morelli M, Galluzzo M, Madonna S, et al. HLA-Cw6 and other HLA-C alleles, as well as MICB-DT, DDX58, and TYK2 genetic variants associate with optimal response to anti-IL-17A treatment in patients with psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;21(2):259–270. doi:10.1080/14712598.2021.1862082

14. Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, Marchlewicz M. The impact of diet and physical activity on Psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15(4):840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

15. Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, Gondo GC, Bell SJ, Griffiths CEM. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):940. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2007

16. Gao J, Shen X, Ko R, Huang C, Shen C. Cognitive process of psoriasis and its comorbidities: from epidemiology to genetics. Front Genetics. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.735124

17. Douroudis K, Ramessur R, Barbosa IA, et al. Differences in clinical features and comorbid burden between HLA-C*06:02 carrier groups in >9000 people with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;142(6):1617–1628.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2021.08.446

18. Di Cesare A, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. The IL-23/TH17 axis in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(6):1339–1350. doi:10.1038/jid.2009.59

19. Basavaraj KH, Ashok NM, Rashmi R, Praveen TK. The role of drugs in the induction and/or exacerbation of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(12):1351–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04570.x

20. Santoleri F, Musicco F, Fulgenzio C, et al. Adherence, persistence and treatment switching in psoriasis. Immunotherapy. 2024;16(9):611–621. doi:10.2217/imt-2023-0343

21. Min S, Wang D, Xia J, Lin X, Jiang G. The economic burden and quality of life of patients with psoriasis treated with biologics in China. J Dermatol Treat. 2023;34(1). doi:10.1080/09546634.2023.2247106

22. Gomes GS, Frank LA, Contri RV, Longhi MS, Pohlmann AR, Guterres SS. Nanotechnology-based alternatives for the topical delivery of immunosuppressive agents in psoriasis. Int J Pharm. 2022;631:122535. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.122535

23. Choon SE, Van De Kerkhof P, Gudjonsson JE, et al. International consensus definition and diagnostic criteria for generalized pustular psoriasis from the international psoriasis council. JAMA dermatol. 2024;160(7):758. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.0915

24. Wu JJ, Kavanaugh A, Lebwohl MG, Gniadecki R, Merola JF. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome: implications for the management and treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(6):797–806. doi:10.1111/jdv.18044

25. Augustin M, Holland B, Dartsch D, Langenbruch A, Radtke MA. Adherence in the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review. Dermatology. 2011;222(4):363–374. doi:10.1159/000329026

26. PPiragine E, Petri D, Martelli A, et al. Adherence and persistence to biological drugs for psoriasis: systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1506. doi:10.3390/jcm11061506

27. Mapp T. Understanding phenomenology: the lived experience. Br J Midwifery. 2008;16(5):308–311. doi:10.12968/bjom.2008.16.5.29192

28. Greenfield B, Jensen GM. Phenomenology: a powerful tool for patient-centered rehabilitation. Phys Ther Rev. 2012;17(6):417–424. doi:10.1179/1743288x12y.0000000046

29. Horne R, Chapman SCE, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080633

30. Stewart SJF, Moon Z, Horne R. Medication nonadherence: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health. 2022;38(6):726–765. doi:10.1080/08870446.2022.2144923

31. Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. Handbook Child Psychol. 2007. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114

32. Navarro JL, Stephens C, Rodrigues BC, et al. Bored of the rings: methodological and analytic approaches to operationalizing Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT model in research practice. J Fam Theory Rev. 2022;14(2):233–253. doi:10.1111/jftr.12459

33. Xia M, Li X, Tudge JRH. Operationalizing urie bronfenbrenner’s process-person-context-time model. Human Dev. 2020;64(1):10–20. doi:10.1159/000507958

34. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000000388

35. Jiang Y, Samah NA, Zhou H. Adolescent patients’ experiences of mental disorders related to school bullying [Letter]. J Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2024;17:4491–4492. doi:10.2147/jmdh.s495261

36. Xiao ZS, Zhou H, Jiang YL, Samah NA. Embracing the complexity of lived experiences in psychiatry research: reflexivity, cultural sensitivity, and emergent design. World J Psych. 2024;14(12):1793–1796. doi:10.5498/wjp.v14.i12.1793

37. Young HN, Len-Rios ME, Brown R, Moreno MM, Cox E. How does patient-provider communication influence adherence to asthma medications? Patient Educ Couns. 2016;100(4):696–702. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.022

38. Kvarnström K, Westerholm A, Airaksinen M, Liira H. Factors contributing to medication adherence in patients with a chronic condition: a scoping review of qualitative research. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(7):1100. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13071100

39. Losi S, Berra CCF, Fornengo R, Pitocco D, Biricolti G, Federici MO. The role of patient preferences in adherence to treatment in chronic disease: a narrative review. Drug Target Insights. 2021;15:13–20. doi:10.33393/dti.2021.2342

40. Kretchy IA, Asiedu-Danso M, Kretchy JP. Medication management and adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and experiences from low-and middle-income countries. Res Social Administrative Pharm. 2020;17(1):2023–2026. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.007

41. Polivy J, Herman CP. If at first you don’t succeed: false hopes of self-change. Am Psychologist. 2002;57(9):677–689. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.57.9.677

42. Maier SF, Seligman ME. Learned helplessness: theory and evidence. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1976;105(1):3–46. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3

43. Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):607–613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

44. Svendsen MT, Andersen KE, Andersen F, Hansen J, Pottegård A, Johannessen H. Psoriasis patients’ experiences concerning medical adherence to treatment with topical corticosteroids. Psoriasis. 2016;6:113–119. doi:10.2147/ptt.s109557

45. Böhm D, Gissendanner SS, Bangemann K, et al. Perceived relationships between severity of psoriasis symptoms, gender, stigmatization and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;27(2):220–226. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04451.x

46. Sánchez‐García V, Hernández‐Quiles R, de‐Miguel‐Balsa E, Giménez‐Richarte Á, Ramos‐Rincón JM, Belinchón‐Romero I. Exposure to biologic therapy before and during pregnancy in patients with psoriasis: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(10):1971–1990. doi:10.1111/jdv.19238

47. Havelin A, Hampton P. Telemedicine and e-Health in the management of psoriasis: improving patient outcomes – a narrative review. Psoriasis. 2022;12:15–24. doi:10.2147/ptt.s323471

48. Alderwick H, Hutchings A, Briggs A, Mays N. The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10630-1

49. Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, Vreeland MG, Wu Y. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Ame J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(6):383–392. doi:10.2165/00128071-200506060-00005

50. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6

51. White CA. Cognitive behavioral principles in managing chronic disease. West J Emergency Med. 2001;175(5):338–342. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.5.338

52. Pourali SP, Nshuti L, Dusetzina SB. Out-of-Pocket costs of specialty medications for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treatment in the Medicare population. JAMA dermatol. 2021;157(10):1239. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3616

53. Jankowiak B, Kowalewska B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Khvorik DF. Stigmatization and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;10(2):285–296. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00363-1

54. KKimball A, Gieler U, Linder D, Sampogna F, Warren R, Augustin M. Psoriasis: is the impairment to a patient’s life cumulative? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(9):989–1004. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03705.x

55. Hedin CRH, Sonkoly E, Eberhardson M, Ståhle M. Inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis: modernizing the multidisciplinary approach. J Internal Med. 2021;290(2):257–278. doi:10.1111/joim.13282

56. Svedbom A, Mallbris L, Larsson P, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognosis in new-onset psoriasis. JAMA dermatol. 2021;157(6):684. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0734

57. Liu Z, Wang X, Ma Y, Lin Y, Wang G. Artificial intelligence in psoriasis: where we are and where we are going. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32(11):1884–1899. doi:10.1111/exd.14938

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

Therapeutic Inertia in the Management of Psoriasis: A Quantitative Survey Among Indian Dermatologists and Patients

Rajagopalan M, Dogra S, Godse K, Kar BR, Kotla SK, Neema S, Saraswat A, Shah SD, Madnani N, Sardesai V, Sekhri R, Varma S, Arora S, Kawatra P

Psoriasis: Targets and Therapy 2022, 12:221-230

Published Date: 25 August 2022