Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 18

Trait Mindfulness, Resilience, Self-Efficacy, and Postpartum Depression: A Dominance Analysis and Serial-Multiple Mediation Model

Authors Mei X , Mei R, Li Y, Yang F, Liang M, Chen Q, Ye Z

Received 13 December 2024

Accepted for publication 25 March 2025

Published 31 March 2025 Volume 2025:18 Pages 743—757

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S509684

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Gabriela Topa

Xiaoxiao Mei,1 Ranran Mei,2 Yan Li,1 Funa Yang,3 Minyu Liang,4 Qianwen Chen,4 Zengjie Ye5

1School of Nursing, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Breast Oncology, Guangzhou Institute of Cancer Research, The Affiliated Cancer Hospital, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 3Nursing Department, The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China; 4School of Nursing, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 5School of Nursing, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Zengjie Ye, Email [email protected]

Background: Postpartum depression affects many women after childbirth, impacting both maternal and child well-being. Psychological traits such as trait mindfulness, resilience, and self-efficacy have been linked to postpartum depression, but their interactions and collective influence are not well understood.

Objective: The study aims to examine the associations between trait mindfulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and postpartum depression.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted from August 2022 to May 2023 using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, the General Self-efficacy Scale, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Dominance analysis, latent profile analysis, and serial-multiple mediation models were employed for data analysis.

Results: Dominance analysis showed that trait mindfulness, resilience, and self-efficacy explained 36.3%, 35.4%, and 28.3% of the variance in postpartum depression, respectively. Three trait mindfulness profiles were identified as mild (23.2%), moderate (55.5%), and high (21.3%). Postpartum women in the mild group exhibited higher postpartum depressive symptoms than those in the moderate and high groups. The effects of trait mindfulness on postpartum depression were significantly mediated by resilience (B=− 0.064, 95% CI − 0.088 to − 0.044), self-efficacy (B=− 0.014, 95% CI − 0.023 to − 0.006), and serial mediation between resilience and self-efficacy (B=− 0.027, 95% CI − 0.040 to − 0.015). Similar significant mediation effects were observed for moderate (resilience: B=− 0.126, 95% CI − 0 .169 to − 0.065, self-efficacy: B=− 0.041, 95% CI − 0.078 to − 0.010, resilience and self-efficacy: B=− 0.053, 95% CI − 0.090 to − 0.023) and high trait mindfulness profiles (resilience: B=− 0.381, 95% CI − 0.514 to − 0.267, self-efficacy: B=− 0.082, 95% CI − 0.139 to − 0.033, resilience and self-efficacy: B=− 0.160, 95% CI − 0.237 to − 0.089) when compared to the mild reference group.

Conclusion: Trait mindfulness significantly impacts postpartum depression and exhibits heterogeneity among postpartum women. The relationship between trait mindfulness and postpartum depression was mediated by resilience and self-efficacy.

Keywords: postpartum depression, resilience, self-efficacy, trait mindfulness

Introduction

Postpartum women experience significant physical, social, and psychological changes after giving birth, making them vulnerable to various postpartum mood disorders, with postpartum depression (PPD) being the most common non-psychotic psychiatric condition.1,2 PPD typically occurs within the first 6 weeks after childbirth,3 and is characterized by symptoms such as sadness, mood swings, changes in appetite and sleep patterns, loss of interest in activities, social withdrawal, and in severe cases, thoughts of harming the baby or oneself.4 A meta-analysis of 565 studies conducted in 80 different regions or countries revealed a global prevalence of approximately 17.4% for PPD,5 while the prevalence reported in China was 20.2%.6 PPD adversely affects both postpartum women and their infants, leading to lower quality of life7,8 and potential developmental issues for children.9 It also impacts maternal-infant bonding10 and paternal mental health,11 placing a burden on families and healthcare systems. Therefore, understanding protective factors against PPD is essential.

One potential protective factor may be trait mindfulness, which refers to an individual’s ability to maintain attention on present-moment experiences with an open and non-judgmental attitude.12 It is relatively stable over time without mindfulness interventions in both non-pregnant and pregnant populations.13,14 The mindful coping model by Garland, Gaylord, and Park (2009) indicated mindfulness can bolster coping processes by augmenting positive reappraisal and engendering self-transcendence, which then results in positive emotions.15 Previous studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between trait mindfulness and depression in non-pregnant populations.16,17 Moreover, Mennitto et al found that pregnant women with higher trait mindfulness tend to experience lower depressive symptoms.18 Additionally, a recent study indicated that trait mindfulness is associated with consistently low depressive symptoms during the perinatal period.13 However, limited attention has been given to the postpartum period, highlighting the need to investigate the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD among postpartum women.

Resilience, characterized as the capacity to effectively cope with uncertainty, stress, and challenges,19 has emerged as a critical factor in promoting psychological well-being and mitigating PPD among postpartum women.20 Concurrently, research suggests that trait mindfulness exhibits promising potential in fostering resilience development, as heightened levels of mindfulness can facilitate the cultivation of individual resilience.21 Moreover, a substantial body of research has demonstrated the mediating role of resilience in the relationship between trait mindfulness and depression in the general population.22,23 To our knowledge, the potential mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on PPD has not been explored.

Self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to complete certain tasks, plays a fundamental role in enhancing individuals’ persistence and effort when confronted with difficulties.24 It has been extensively recognized as a critical factor in facilitating successful adaptation to new roles25 and is acknowledged as a significant determinant of positive mental health among postpartum women.26,27 Previous studies have found that self-efficacy plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between trait mindfulness and depression,28 as well as in the relationship between resilience and depression among non-pregnant populations.29 Additionally, the relationship between resilience and self-efficacy among postpartum women is significant, suggesting that resilience and self-efficacy are closely intertwined in influencing maternal mental health outcomes.30 However, the mediating role of self-efficacy in the association between trait mindfulness and PPD, as well as the serial mediating effect of resilience and self-efficacy between trait mindfulness and PPD, has not been explored among postpartum women.

It is of utmost importance to ascertain the impact of the trait mindfulness, resilience, and self-efficacy on PPD. Such understanding is crucial for exploring the mechanisms that influence depressive symptoms in postpartum women, allowing for the development of unique emotional regulation strategies aimed at alleviating depression from a multidimensional perspective. Additionally, it provides a theoretical framework for addressing the mental health challenges faced by this population. In light of this, we propose a conceptual model by integrating the mindful coping model, as shown in Figure 1. Our objectives include ranking the significance of the three protective factors and investigating the mediating roles of resilience and self-efficacy in the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD. We hypothesized that (1) trait mindfulness would emerge as the foremost protective factor in PPD; (2) trait mindfulness may exhibit heterogeneity; (3) resilience would play a mediating role between trait mindfulness and PPD; (4) self-efficacy would mediate the association between trait mindfulness and PPD; and (5) resilience and self-efficacy would jointly mediate the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual model of the relationships between trait mindfulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and postpartum depression. |

Methods

Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from August 2022 to May 2023 at a tertiary hospital in Guangzhou, China. Women were recruited during their routine postpartum clinical visits, typically occurring around six weeks postpartum. A convenience sampling method was used. Eligible women were approached by the researchers and provided with adequate time to consider their participation. After obtaining informed consent, researchers guided participants in completing the questionnaire. To ensure independent completion of the questionnaire, researchers monitored the process from a distance, allowing participants to fill it out without assistance while remaining available to address any questions. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥20 years; (2) being within 6 weeks postpartum; (3) having healthy and full-term infant (s); (4) being able to communicate fluently in Mandarin; (5) willing to participate in this study. Women with severe mental illness or serious comorbidities or complications were excluded from this study. To estimate the minimum sample size required for detecting a significant serial-multiple mediation effect, the “Monte Carlo-based statistical power analysis for mediation models” was utilized.31 Based on previous research,32–34 we assumed a standard deviation of 9 for mindfulness, 7 for resilience, 6 for self-efficacy, and 5 for postpartum depression, with a correlation coefficient of 0.3 between these variables, an alpha level of 0.05, and a desired statistical power of 0.8, then at least 262 participants were required for the study. The STROBE (The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed (see Supplementary File 1 for details).

Instruments

Sociodemographic and Obstetrical Characteristics

Based on previous literature,35,36 we collected socio-demographics (age, academic degree, working status, marital status, monthly average household income, place of residence) and obstetrical information (parity, pregnancy intention, and mode of delivery).

Mindfulness

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) is a 15-item single-dimension scale developed by Brown and Ryan in 2003 to evaluate individuals’ trait mindfulness.12 It was translated into Chinese by Deng et al in 2011.37 Participants rated their responses on a frequency scale from 1 to 6, where 1 meant “almost always”, 2 was “very frequently”, 3 indicated “frequently”, 4 stood for “occasionally”, 5 represented “rarely”, and 6 signified “almost never”. Higher scores indicate greater levels of mindful awareness during those moments. The reliability of the Chinese version of the MAAS has been demonstrated,37 and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.875 in our study, suggesting good internal consistency.

Resilience

The 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) is a concise adaptation of the original 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, developed by Connor and Davidson.38 The shorter version was validated by Campbell-Sills and Stein and ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of resilience.39 Ye et al validated the Chinese version,40 and it has been previously utilized in our earlier research.33,41 In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to be 0.942, indicating a robust internal consistency of the scale.

Self-Efficacy

The General Self-efficacy Scale (GSES), developed by Zhang and Schwarzer in 1995,42 is widely used to assess an individual’s self-confidence in diverse situations.43 This scale consists of 10 items and adopts a 4-Likert response format, with total scores ranging from 10 to 40. The response options are defined as follows: 1 for “completely incorrect”, 2 for “somewhat correct”, 3 for “mostly correct”, and 4 for “completely correct”. The Chinese version of the GSES has demonstrated favorable reliability and validity,44 and our prior studies have successfully applied this scale.33,45,46 The Cronbach’s alpha for the GSES in the current study was 0.931, indicating a high level of internal consistency.

Postpartum Depression

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), developed by Cox et al in 1987,47 is the most commonly employed screening tool worldwide for postpartum depression.48 Comprising 10 items, the EPDS employs a 4-Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 3), with higher scores representing a higher level of depression. The Chinese version of the EPDS was translated by Lee et al49 and has been utilized in research on maternal postpartum depression in China.50 In the present, the Cronbach’s alpha for the EPDS study was calculated to be 0.824, indicating a satisfactory level of internal consistency.

Statistical Analyses

First, categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations. Independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to investigate differences in sociodemographic and obstetrical characteristics of participants’ EPDS scores. Linear regression and Pearson’s correlation analysis were conducted to explore the relationships among trait mindfulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and postpartum depression. Prior to conducting the linear regression, the assumptions of normality and independence were assessed.

Second, dominance analysis was conducted to determine the relative importance of trait mindfulness, resilience, and self-efficacy on postpartum depression in this study. The procedure of dominance analysis involves three main steps: (1) A multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the optimal regression model, known as the full model, that could effectively predict postpartum depression. All possible sub‐models were examined, with the number of sub‐models being 2p‐1, where p represents the number of predictors in the full model; (2) Hierarchical regression was employed to calculate the incremental contribution (R2) of each predictor within the full model by systematically adding each sub‐model while excluding its variables. By comparing the R2 value when both sides of ΔR2 are non‐null, the final relationship between the predictors is determined; (3) The total average contribution of the predictors and the percentage of the full model coefficients were computed.51 Higher R2 values and percentage of total variance explained correspond to greater relative importance for the respective predictor.52

Third, an unconditional latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted to identify subgroups of postpartum women’s trait mindfulness. It began with a one-class model, continuing until fit indices could not be improved. The model fit was determined based on the following indices, including Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), and Sample-Size Adjusted BIC (aBIC).53 The accuracy of model classification was determined by Entropy.54 Its value ranged from 0 to 1 and it is generally considered that when Entropy was greater than 0.8, the classification accuracy was higher than 90%. In addition, Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMRT) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) were used to compare the differences between two adjacent category models.55 If significant (P<0.05), it meant that one more category was more appropriate, ie, the K-category model was better than the K-1 category model.

Fourth, the Bayesian independent samples t-test was applied to compare the postpartum depression (EPDS total scores) among the LPA-based postpartum women with different trait mindfulness profiles (the alternative hypothesis H1: there are between-group differences; the null hypothesis H0: there are no between-group differences). If the Bayes factor BF10 = 10, then the alternative hypothesis is 10 times more likely to hold under the current data than the null hypothesis.56

Fifth, serial mediation analysis was conducted to examine the mediating model. Given that the data were based on self-reports, the potential issue of common method variance (CMV) was assessed by Harman’s single-factor test.57 Trait mindfulness was identified as the independent variable (X), while postpartum depression served as the dependent variable (Y). Resilience (M1) and self-efficacy (M2) were recognized as the mediators in the model. The total, direct, and indirect effects were estimated and 95% CI was calculated with 5000 bootstrapping resamples.

SPSS (V.26.0), Mplus (V.8.1), and JASP (V.0.18.3.0) were used for all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set as a P value less than 0.05.

Ethics

The study was performed per the national legislation and institutional requirements. All methods were performed per the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics review committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (No: K-2022-024) and was conducted as part of the Be Resilient to Postpartum Depression (BRPD), with registration number ChiCTR2100048465. Before the formal investigation, written consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 635 women were invited to participate in the study, with 598 agreeing to take part and completing the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 94.17%. The average age of the 598 postpartum women was 30.13 years (SD = 4.04) and the mean EPDS score was 9.21 ± 4.52. Durbin–Watson test indicated that the assumption of independence of residuals was met, and the histogram of residuals demonstrated that the data followed a normal distribution (see Figures S1–S3 for details). Furthermore, trait mindfulness (P<0.001), resilience (P<0.001), and self-efficacy (P<0.001) significantly influenced postpartum depression. Other details are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographic and Relevant Variables Differences in Scores of Postpartum Depression (N = 598) |

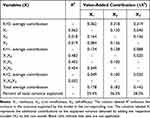

Dominance Analysis

In Table 2, the dominance analysis revealed that trait mindfulness accounted for the highest proportion of total variance (36.3%), followed by resilience (35.4% of known variance) and self-efficacy (28.3% of known variance) in predicting postpartum depression. Consequently, trait mindfulness was included in the latent profile analysis, and trait mindfulness (independent variable), resilience (Mediator 1), self-efficacy (Mediator 2), and postpartum depression (Dependent variable) were included in the subsequent serial mediation analysis.

|

Table 2 The Value-Added Contribution, Average Contribution and Total Average Contribution of Each Predictor Variable (N = 598) |

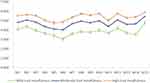

Latent Profile Analysis

In Table 3, AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC values decreased in line with an increasing number of profiles. Meanwhile, LMRT indicated that a three-profile model was better than a two-profile one (P=0.0031), while the difference between a three-profile model and a four-profile one was not significant (P=0.0763). Thus, according to the parsimonious guideline, we finally chose the three-profile solution. The subgroups were named as mild trait mindfulness group (23.2%), moderate trait mindfulness group (55.5%), and high trait mindfulness group (21.3%) and visualized in Figure 2. The EPDS scores were significantly different between the mild group and moderate group (BF10=2.29e+9), mild group and high group (BF10=5.47e+35), and moderate group and high group (BF10=5.13e+22). These findings were confirmed by Bayesian independent sample t-test analysis. More details are demonstrated in Figure 3A–E.

|

Table 3 Fitting Index and Group Size of Latent Profile Analysis (N = 598) |

|

Figure 2 Three-profile model for trait mindfulness in postpartum women. |

Serial Mediation Analysis

The common method bias test indicated a total of eleven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 and the first factor accounted for 29.238% of the total variance, so the common method bias was negligible. Postpartum depression was significantly correlated with resilience (r=−0.602, P<0.001), trait mindfulness (r=−0.564, P<0.001), and self-efficacy and (r=−0.564, P<0.001), other results from Pearson’s correlation analysis are given in Figure 4A.

Figure 4B illustrates that trait mindfulness (continuous variable) was associated with resilience (β=0.314, P<0.001) and self-efficacy (β=0.090, P<0.001). Both resilience and self-efficacy demonstrated significant effects on postpartum depression (resilience, β=−0.205, P<0.001; self-efficacy, β=−0.153, P<0.001). According to Table 4, the indirect effect of trait mindfulness (continuous variable) through resilience and self-efficacy on postpartum depression was significant (B=−0.027, 95% CI −0.040 to −0.015).

|

Table 4 Trait Mindfulness and Postpartum Depression: Test of Mediating Effect and Effect Size (N = 598) |

When trait mindfulness was treated as a categorical variable, taking mild trait mindfulness as the reference category, the mediating effect of resilience, self-efficacy, and the combined mediation of resilience and self-efficacy were observed to be −0.126, −0.041, and −0.053, respectively, with 95% Bootstrap confidence intervals of (−0.169, −0.065), (−0.078, −0.010), and (−0.090, −0.023). Importantly, all of these confidence intervals excluded the value of “0”, indicating a significant mediating effect. Similar findings were observed in the high trait mindfulness group, as shown in Table 4, highlighting the mediating roles of resilience and self-efficacy between different trait mindfulness profiles and postpartum depression.

Discussion

In this study, we employed dominance analysis to explore the relative importance of trait mindfulness, resilience, and self-efficacy to PPD. Additionally, we utilized latent profile analysis to identify the heterogeneity of trait mindfulness and serial mediation analysis was conducted to examine the mediating role of resilience and self-efficacy in the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD. The findings of this study enhanced our understanding of the associations among trait mindfulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and PPD in women during the postpartum period, contributing to the existing body of knowledge in this field.

One of the key findings of our study was that trait mindfulness had the strongest protective effect on PPD, followed by resilience and self-efficacy, which validated hypothesis 1. This finding was consistent with previous research,13,16 highlighting the crucial role of trait mindfulness in promoting mental well-being and reducing depressive symptoms. One potential explanation for this finding is that higher levels of trait mindfulness enable women to recognize and accept their thoughts and emotions, which in turn equips them with better-coping mechanisms for managing the challenges and emotional fluctuations experienced during the postpartum period, ultimately reducing the risk of developing PPD.58 Additionally, our analysis revealed heterogeneity in the level of trait mindfulness among postpartum women, validating hypothesis 2. LPA identified three distinct profiles of trait mindfulness: mild, moderate, and high, which aligns with a study by Echabe-Ecenarro et al (2023) involving 535 pregnant women.59 Importantly, significant differences in EPDS scores were found among these trait mindfulness profiles, with the high trait mindfulness group displaying the lowest EPDS scores. These findings suggested the potential for incorporating mindfulness-based interventions into PPD prevention programs for postpartum women with lower levels of trait mindfulness.58 For instance, Sun et al (2021) conducted an 8-week smartphone-based mindfulness training for pregnant women and reported significant improvement in depression, anxiety, and positive affect at 6 weeks after delivery.60

Furthermore, the present study confirmed hypothesis 3 by demonstrating that the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD was mediated by resilience. The results indicated that higher levels of trait mindfulness were associated with greater resilience, which, in turn, resulted in lower levels of PPD symptoms. This finding can be explained by the notion that postpartum women with high levels of mindfulness possess the ability to effectively comprehend and address their negative emotions when faced with stressful life events during the postpartum period.61 This adaptive response plays a crucial role in mitigating the harmful effects of challenges and bolstering resilience.62 In contrast, women with low levels of trait mindfulness may struggle to acknowledge and accept their negative emotions, leading to their accumulation over time.61 Consequently, their resilience diminishes as they attempt to minimize the adverse consequences of challenging circumstances.63 On the other hand, women with elevated levels of resilience tend to respond positively and successfully overcome crises by maintaining steadfast beliefs in the face of stress or adversity, thereby reducing the likelihood of experiencing PPD.20 Therefore, integrating mindfulness into healthcare education holds immense potential for enhancing the resilience of postpartum women, empowering them to effectively navigate the complexities and demands inherent in the postpartum period.64 This proactive approach has the potential to promote the overall well-being of postpartum women and reduce the incidence of PPD.

Additionally, self-efficacy was tested to mediate the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD, validating hypothesis 4. Specifically, higher levels of trait mindfulness were linked to increased self-efficacy, which, in turn, was associated with lower levels of PPD. Postpartum women with high levels of mindfulness could consciously choose to shift their attention away from negative aspects and redirect it towards more beneficial thoughts and emotions.61 By actively engaging in this process, postpartum women can gradually decrease the influence of harmful thoughts and increase their belief in their abilities, thus enhancing self-efficacy.65 On the other hand, an increased level of self-efficacy is anticipated to serve as a protective factor against PPD in postpartum women by bolstering feelings of control, self-confidence, and the use of adaptive coping strategies.27 Thus, trait mindfulness acts as a buffer against low self-efficacy, which, in turn, exerts its beneficial effects on PPD.

Finally, when investigating the relationship between trait mindfulness and PPD, the study uncovered a significant pathway involving chain mediation from resilience to self-efficacy. This finding is consistent with previous research that has highlighted the association between resilience and self-efficacy.29 Individuals who possess higher levels of resilience tend to exhibit enhanced self-efficacy, persistence, and confidence in their abilities to overcome challenges and accomplish desired outcomes.66 This implies that resilience plays a pivotal role in bolstering postpartum women’s belief in their capabilities, and subsequently elevating their self-efficacy levels. Moreover, the identified chain mediation effect sheds light on the intricate interplay among these psychological constructs and provides insights into the potential mechanisms through which trait mindfulness can impact PPD. By fostering resilience and subsequently enhancing self-efficacy, interventions aimed at cultivating mindfulness skills can help buffer against the development of PPD.67

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. Firstly, the inclusion of postpartum women solely from one tertiary hospital may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader postpartum population. Therefore, it is crucial to validate these findings using a larger and more diverse sample. Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of this study prevents the establishment of causal relationships between the variables. Future findings from our cohort study, covering the first trimester, second trimester, third trimester, and a 42-day postpartum period, can provide more robust evidence for the observed associations. Thirdly, reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for social desirability bias and may lead to an under- or overestimation of the reported outcomes. The use of objective measures or multiple data sources could enhance the reliability and validity of the results. Lastly, the serial mediation model did not consider several potential confounders, such as perceived stress, sleep quality, and personality traits, due to limitations in scale burden. The omission of these variables may have influenced the estimation of the associations observed. Future studies should take these factors into account to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships under investigation.

Implications for Research and Practice

Our study yielded significant findings regarding the protective effect of trait mindfulness on PPD. To further investigate the specific components and mechanisms through which trait mindfulness influences PPD, future research endeavors can adopt a multidimensional approach to measure trait mindfulness. One promising instrument for this purpose is the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, which encompasses the dimensions of observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reactivity.68 By employing this comprehensive measurement tool, researchers can delve deeper into the nuances of trait mindfulness and its impact on PPD.

Additionally, our study highlighted the importance of resilience and self-efficacy alongside trait mindfulness to PPD. Healthcare professionals and educators working with postpartum women can leverage these findings to develop targeted interventions, including mindfulness-based interventions, resilience-building strategies, and self-efficacy enhancement programs. By equipping women with the necessary tools and resources to effectively navigate the challenges of the postpartum period, these interventions hold immense potential for preventing and managing PPD. Strengthening the overall well-being of postpartum women through these interventions can significantly reduce the incidence and severity of PPD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides evidence supporting the strongest protective effect of trait mindfulness against PPD while also highlighting the presence of heterogeneity in postpartum women’s trait mindfulness. The findings indicated that the impact of trait mindfulness on PPD is mediated by resilience and self-efficacy. The serial mediation results further suggest that resilience and self-efficacy may amplify the positive effects of trait mindfulness on PPD. Consequently, future research should continue to investigate the underlying mechanisms linking trait mindfulness, resilience, self-efficacy, and PPD, with a focus on developing targeted interventions that leverage these factors to enhance the well-being of postpartum women.

Data Sharing Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study, including sociodemographic and obstetrical characteristics and responses from the MAAS, CD-RISC-10, GSES, and EPDS, are available from the corresponding author, Prof. Zengjie Ye [email protected], for two years following publication upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was approved by the ethics review committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (No: K-2022-024) and was part of the “Be Resilient to Postpartum Depression” study (Registration number: ChiCTR2100048465, registered on 09/07/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were assured that their information would remain confidential. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the nurses from the participating hospital for supporting data collection and all the participants for completing the survey.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72274043 and 71904033), Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CACM (No. 2021-QNRC2-B08), Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (No. 2023A04J2473).

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Garapati J, Jajoo S, Aradhya D, et al. Postpartum mood disorders: insights into diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42107.

2. Rupanagunta GP,Nandave M, Rawat D, Upadhyay J, Rashid S, Ansari MN. Postpartum depression: aetiology, pathogenesis and the role of nutrients and dietary supplements in prevention and management. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(7):1274–1293.

3. Wu D, Jiang L, Zhao G. Additional evidence on prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression in China: a study of 300,000 puerperal women covered by a community-based routine screening programme. J Affective Disorders. 2022;307:264–270. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.011

4. Santos HP Jr, Kossakowski JJ, Schwartz TA, et al. Longitudinal network structure of depression symptoms and self-efficacy in low-income mothers. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191675. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191675

5. Wang Z, Liu J, Shuai H, et al. Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):543. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01663-6

6. Wang X, Zhang L, Lin X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depressive symptoms at 42 days among 2462 women in China. J Affect Disord. 2024;350:706–712. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.135

7. Almuqbil M, Kraidiye N, Alshmaimri H, et al. Postpartum depression and health-related quality of life: a Saudi Arabian perspective. PeerJ. 2022;10:e14240. doi:10.7717/peerj.14240

8. Abdollahi F, Zarghami M. Effect of postpartum depression on women’s mental and physical health four years after childbirth. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(10):1002–1009. doi:10.26719/2018.24.10.1002

9. Goodman JH. Perinatal depression and infant mental health. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;33(3):217–224. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2019.01.010

10. Lindensmith R. Interventions to improve maternal-infant relationships in mothers with postpartum mood disorders. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2018;43(6):334–340. doi:10.1097/NMC.0000000000000471

11. Duan Z, Wang Y, Jiang P, et al. Postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: a structural equation model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):537. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03228-9

12. Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

13. Hulsbosch LP, Boekhorst MG, Endendijk J, et al. Trait mindfulness scores are related to trajectories of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;151:166–172. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.04.023

14. Jensen CG, Krogh SC, Westphael G, Hjordt LV, et al. Mindfulness is positively related to socioeconomic job status and income and independently predicts mental distress in a long-term perspective: Danish validation studies of the five-factor mindfulness questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(1):e1–e20.

15. Garland E, Gaylord S, Park J. The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore. 2009;5(1):37–44.

16. Chen J, Zhang C, Wang Y, et al. A longitudinal study of childhood trauma impacting on negative emotional symptoms among college students: a moderated mediation analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27(3):571–588. doi:10.1080/13548506.2021.1883690

17. Duraney EJ, Schirda B, Nicholas JA, et al. Trait mindfulness, emotion dysregulation, and depression in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;59:103651. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.103651

18. Mennitto S, Ditto B, Da Costa D. The relationship of trait mindfulness to physical and psychological health during pregnancy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;42(4):313–319. doi:10.1080/0167482X.2020.1761320

19. Sisto A, Vicinanza F, Campanozzi LL, Ricci G, Tartaglini D, Tambone V. Towards a transversal definition of psychological resilience: a literature review. Medicina. 2019;55(11):745.

20. Baattaiah BA, Alharbi MD, Babteen NM, et al. The relationship between fatigue, sleep quality, resilience, and the risk of postpartum depression: an emphasis on maternal mental health. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):10. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01043-3

21. Shi K, Feng G, Huang Q, et al. Mindfulness and negative emotions among Chinese college students: chain mediation effect of rumination and resilience. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1280663. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1280663

22. Bajaj B, Khoury B, Sengupta S. Resilience and stress as mediators in the relationship of mindfulness and happiness. Front Psychol. 2022;13:771263. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.771263

23. Pérez-Aranda A, García-Campayo J, Gude F, et al. Impact of mindfulness and self-compassion on anxiety and depression: the mediating role of resilience. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(2):100229. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100229

24. Bandura A, Adams NE, Beyer J. Cognitive processes mediating behavioral change. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977;35(3):125–139. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.35.3.125

25. Dlamini LP, Hsu -Y-Y, Shongwe MC, et al. Maternal self-efficacy as a mediator in the relationship between postpartum depression and maternal role competence: a cross-sectional survey. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2023;68(4):499–506. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13478

26. Savory NA, Hannigan B, John RM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of poor mental health among pregnant women in Wales using a cross-sectional survey. Midwifery. 2021;103:103103. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103103

27. Mohammad KI, Sabbah H, Aldalaykeh M, et al. Informative title: effects of social support, parenting stress and self-efficacy on postpartum depression among adolescent mothers in Jordan. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(23–24):3456–3465. doi:10.1111/jocn.15846

28. Sharma PK, Kumra R. Relationship between mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress: mediating role of self-efficacy. Pers Individ Dif. 2022;186:111363. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111363

29. Wang L, Li M, Guan B, et al. Path analysis of self-efficacy, coping style and resilience on depression in patients with recurrent schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023;19:1901–1910. doi:10.2147/NDT.S421731

30. Tuxunjiang X, Wumaier G, Zhang W, et al. The relationship between positive psychological qualities and prenatal negative emotion in pregnant women: a path analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1067757. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1067757

31. Schoemann AM, Boulton AJ, Short SD. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychol Personal Sci. 2017;8(4):379–386. doi:10.1177/1948550617715068

32. Sharifi-Heris Z, Amiri-Farahani L, Shahabadi Z, et al. Impact of social support and mindfulness in the associations between perceived risk of COVID-19 acquisition and pregnancy outcomes in Iranian population: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):328. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01371-4

33. Mei X, Mei R, Liu Y, et al. Associations among fear of childbirth, resilience and psychological distress in pregnant women: a response surface analysis and moderated mediation model. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1091042. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1091042

34. Zheng J, Sun K, Aili S, et al. Predictors of postpartum depression among Chinese mothers and fathers in the early postnatal period: a cross-sectional study. Midwifery. 2022;105:103233. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103233

35. Chen Q, Li W, Xiong J, Zheng X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with postpartum depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2219.

36. Sarı O, Dağcıoğlu BF, Akpak YK, Yerebatmaz N, İleri A. Planned and unplanned pregnancy and its association with coping styles and life quality. Health Care Women Int. 2021;44:1–11.

37. Deng Y-Q, Li S, Tang -Y-Y, et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese translation of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Mindfulness. 2012;3(1):10–14. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0074-1

38. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi:10.1002/da.10113

39. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. doi:10.1002/jts.20271

40. Ye ZJ, Qiu HZ, Li PF, et al. Validation and application of the Chinese version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC-10) among parents of children with cancer diagnosis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;27:36–44. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2017.01.004

41. Mei X, Du P, Li Y, et al. Fear of childbirth and sleep quality among pregnant women: a generalized additive model and moderated mediation analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):931. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-05435-y

42. Zhang JX, Schwarzer R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: a Chinese adaptation of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia. 1995;38(3):174–181.

43. Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–457. doi:10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457

44. Chunmei D, Yong C, Long G, et al. Self efficacy associated with regression from pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and low back pain following pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):122. doi:10.1186/s12884-023-05393-z

45. Mei X, Wang H, Wang X, et al. Associations among neuroticism, self-efficacy, resilience and psychological distress in freshman nursing students: a cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e059704. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059704

46. Mei XX, Wang HY, Wu XN, et al. Self-efficacy and professional identity among freshmen nursing students: a latent profile and moderated mediation analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:779986. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.779986

47. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

48. Ezirim N, Younes LK, Barrett JH, et al. Reproducibility of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale during the postpartum period. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40(2):194–200. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1727226

49. Lee DT, Yip SK, Chiu HF, et al. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:433–437. doi:10.1192/bjp.172.5.433

50. Li Q, Yang S, Xie M, et al. Impact of some social and clinical factors on the development of postpartum depression in Chinese women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):226. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-02906-y

51. Azen R, Budescu DV. Comparing predictors in multivariate regression models: an extension of dominance analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31(2):157–180. doi:10.3102/10769986031002157

52. Luo W, Azen R. Determining predictor importance in hierarchical linear models using dominance analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2013;38(1):3–31. doi:10.3102/1076998612458319

53. Simpson EG, Vannucci A, Ohannessian CM. Family functioning and adolescent internalizing symptoms: a latent profile analysis. J Adolesc. 2018;64:136–145. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.02.004

54. Shafiq M, Malhotra R, Teo I, et al. Trajectories of physical symptom burden and psychological distress during the last year of life in patients with a solid metastatic cancer. Psychooncology. 2022;31(1):139–147. doi:10.1002/pon.5792

55. Wang M, Deng Q, Bi X, et al. Performance of the entropy as an index of classification accuracy in latent profile analysis: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2017;49(11):1473. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.01473

56. Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90(430):773–795. doi:10.1080/01621459.1995.10476572

57. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

58. Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT, et al. Benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):140. doi:10.1186/s12884-017-1319-3

59. Echabe-Ecenarro O, Orue I, Calvete E. Dispositional mindfulness profiles in pregnant women: relationships with dyadic adjustment and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1237461. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1237461

60. Sun Y, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Effectiveness of smartphone-based mindfulness training on maternal perinatal depression: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e23410. doi:10.2196/23410

61. Luberto CM, Park ER, Goodman JH. Postpartum outcomes and formal mindfulness practice in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal women. Mindfulness. 2018;9(3):850–859. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0825-8

62. Godbout N, Paradis A, Rassart C-A, et al. Parents’ history of childhood interpersonal trauma and postpartum depressive symptoms: the moderating role of mindfulness. J Affect Disord. 2023;325:459–469. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.007

63. Van Haeken S, Braeken MAKA, Horsch A, et al. Development of a resilience-enhancing intervention during and after pregnancy: a systematic process informed by the behaviour change wheel framework. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):267. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01301-4

64. Abbass-Dick J, Sun W, Stanyon WM, et al. Designing a mindfulness resource for expectant and new mothers to promote maternal mental wellness: parents’ knowledge, attitudes and learning preferences. J Child Family Stud. 2020;29(1):105–114. doi:10.1007/s10826-019-01657-5

65. Abdolalipour S, Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi S, Mashayekh-Amiri S, et al. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on self-efficacy and fear of childbirth in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Affective Disorders. 2023;333:257–270. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.020

66. Xu Y, Yang G, Yan C, et al. Predictive effect of resilience on self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: the moderating role of creativity. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1066759. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1066759

67. Min W, Jiang C, Li Z, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy on postpartum mental health: a meta-analysis. J Affective Disorders. 2023;331:452–460. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.03.053

68. Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2025 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, 4.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

Recommended articles

Mediating Effect of Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Perceived Social Support and Resilience in Patients with Recurrent Schizophrenia in China

Wang LY, Li MZ, Jiang XJ, Han Y, Liu J, Xiang TT, Zhu ZM

Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2022, 18:1299-1308

Published Date: 1 July 2022