Assistant Professor Stephen Terry Speaks on his NBER Working Paper: COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty

As the pandemic started, macroeconomists began to grapple with how to think of the coronavirus. Is it a “demand shock” causing people to buy less stuff? Is it a “supply shock” preventing businesses from producing as much stuff? Or is it some other factor affecting our financial network, supply chains, or trade? The answers matter, because policymakers need to understand how to respond to this deep recession. Unfortunately, the virus likely created a mix of influences on all of the factors above, among others. But by focusing on narrow, well defined questions we can still make progress as economists.

For years I’ve been a part of a research community studying economy-wide fluctuations in “uncertainty.” Uncertainty broadly refers to the level of perceived future economic risk or ambiguity. Measures of uncertainty typically increase during downturns. Concrete evidence, drawn from my papers among others, suggests that this higher uncertainty negatively affects the economy. Afraid of uncertainty, people may buy less. And firms may produce less at the same time, combining “demand” and “supply” shocks into one unappealing package.

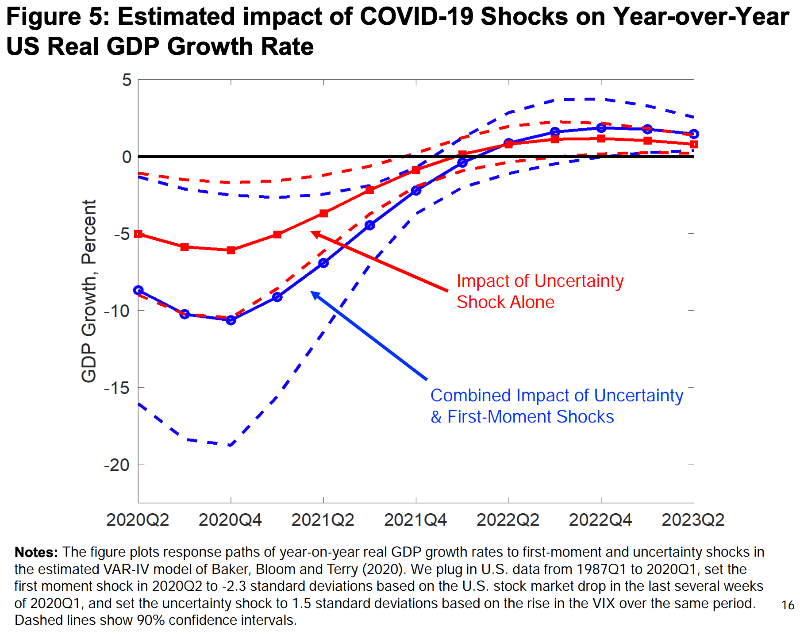

In a recent NBER working paper my collaborators and I used our own high-quality, real-time, representative business survey evidence combined with stock market swings to document an unprecedentedly quick recent spike in uncertainty. In a calculation based on our previous research, we also produced a forecast of US output growth based on the increased uncertainty. We didn’t come to happy conclusions. We project deep declines with an overall loss of around 10% of US output over the course of the year. However, as well grounded or “official” as such forecasts might seem, it’s important for everyone — policymakers, economists, students, and the public — to understand that substantial uncertainty over the future still abounds.

Find the paper here: https://www.nber.org/papers/w26983