Making History: Sybil Morial

Sybil Morial’s memoir remembers the New Orleans that she helped to change

By Susan Seligson

Photograph by Cydney Scott

Sybil Haydel Morial’s expression is wistful as she eases her gold BMW through the grand Parisian-style gates of New Orleans’ City Park. “We just wanted to see what was in here.” The 83-year-old widow of the city’s first black mayor, Morial is telling the story, ever crisp in her mind, of how she and her lifelong friend, the civil rights leader Andrew Young, dared as children to pedal their bikes into the inner sanctum of this vast and verdant wonderland—a 1,300-acre expanse of spreading ash trees, live oaks, gazebo-studded lawns, and a lake, every inch of it then off limits to blacks. As she approaches the palatial New Orleans Museum of Art, Morial veers right and points. “There. That’s as far as we got.” Here the pair was intercepted by police and escorted back to the street, feeling fortunate not to have landed in jail.

Witness to Change: From Jim Crow to Political Empowerment

The author of a memoir titled Witness to Change: From Jim Crow to Political Empowerment (John F. Blair, 2015), with a foreword written by Young, Morial (SED’52,’55), a retired educator and longtime community and civil rights activist, put pen to paper during her eight years of post-Katrina exile living with her daughter in Baton Rouge. It was poetic justice—“a kind of vindication”—that moved Morial to choose the art museum as the venue for her recent book party, which filled its auditorium to overflowing. Today, going on three years back in her rebuilt, modern home overlooking Bayou St. John, she’s still sorting out her surviving possessions. “The house was under three feet of water and then it burned,” says Morial, who is the first to say she was one of the lucky ones. She keeps up a busy schedule with book events and nonprofit board meetings, but loves to sit in her yard catching a breeze as the canal waters flow calmly by, the bayou’s pre-Katrina wildlife replaced by tourists in rental kayaks.

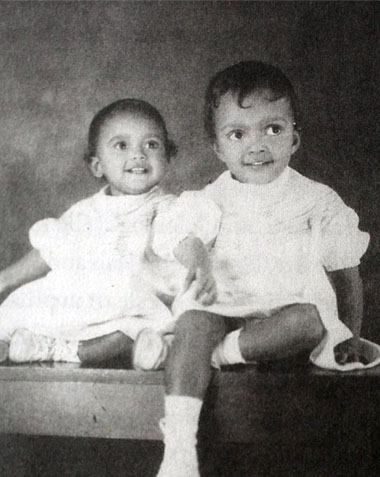

Sybil (right), at age one, and her two-year-old sister Jean, in 1933. Photo courtesy of Sybil Haydel Morial.

“I thought we’d be gone three days, maybe three weeks,” she says. “All those years of photos and memorabilia are mostly gone.” The mother of five describes writing her stories, about growing up in the Seventh Ward in a bungalow built “by a freeborn man of color” and about her first long-distance train ride, when a curtain was drawn around the table where she and her sister were sitting “so the white people didn’t have to look at us,” as merely cathartic initially. She writes about her forming a black women’s voters group, and about journeying to Liberia for the inauguration of President William R. Tolbert, Jr. And she chronicles her late husband’s political struggles as the very legality of his mayoral campaign is challenged.

At the urging of friends and with a few creative writing courses under her belt, she refined those stories into a candid, absorbing book. “It is a book about heroes, written by one,” says Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Harvard’s Alphonse Fletcher University Professor. And Donna Brazile, a television commentator and vice chair of the Democratic National Committee, reminds readers in her blurb on the book jacket that Morial was more than a “witness”—“This charming, gritty gentle-woman was on the front lines in challenging a segregated South.”

The petite Morial has the elegant bearing of someone who has led a public life, making the acquaintance of several sitting US presidents and speaking out for equality in and beyond this most unbuttoned, intimate, and racially complicated of Southern metropolises, where the colossal Ernest N. Morial Convention Center on the banks of the Mississippi bears the name of her late husband. A longtime member of the board of the Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong Summer Jazz Camp and a founder of the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans, Morial was a creator of Symphony in Black, a five-year project to bring in black musicians and conductors to attract black audiences to the New Orleans Symphony.

Her face retains the wary intensity of her book’s cover photo, salvaged from a moldy manila folder in an upstairs desk drawer. It was taken during her years at BU, where she transferred after two years at Xavier College and where she went on to earn a master’s in education. From the time she was a child growing up in an educated, upper-middle-class family, a family that gave their children the rich cultural life denied them publicly in the Jim Crow South, her parents always assured her things would change. Morial hopes her book will help a new generation of both whites and blacks grasp how hard a road it was, and how high the stakes.