news

L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle

Claude Schopp

L'Origine du monde: Vie du modèle

Paris: Editions Phébus, 2018. 152 pp.; 8 color ills.

$14.29

978-2752911780

L’Origine du monde was completed by the French painter Gustave Courbet in 1866. The painting presents a female nude lying against a bedspread. Her thighs open toward us, her jaundiced torso entangled in a white bedsheet. The edge of the canvas cuts into her thighs, truncating her limbs so that her torso occupies the entire canvas; her head, arms, and legs lie outside the frame. This cropping brings an unequivocal focus to the central element of the composition: the woman’s unshaven pubis mons and open labia. Despite the visual candidness of the painting, very little is certain about its history. L’Origine du monde was commissioned by its original owner, the Ottoman diplomat Khalil Bey, and went missing when the collector lost his fortune. The painting resurfaced in the mid-1950s and was purchased at auction by the famous psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. From the painting’s beginnings to its current hanging in the Musée d’Orsay, one question has stupefied the predominantly male researchers drawn to the work: ‘Who is the woman in the painting?’[1]

This question about Courbet’s model is the focus of a recent book by the French literature historian Claude Schopp. Entitled L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, the book revolves around Schopp’s purported discovery of the woman’s identity, the Parisian dancer Constance Quéniaux. The book’s introduction explains how Schopp came upon this information; her name was buried deep within the stacks at the Bibliothèque nationale inside a letter written by Alexander Dumas. From there, Schopp defends his argument by presenting a careful account of his research, the letters that he reviewed and transcribed as well as his theories about the relationships between Courbet and Khalil Bey and between Khalil Bey and Quéniaux.

The second part of the book can be described as a micro-history. Schopp’s L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, functions as a precious document of the life of Quéniaux, a woman whom few would have found interesting if not for her status as the model in Courbet’s infamous painting. His biography of her takes pains to illustrate details about the documents that defined her life, from her birth certificate, to a photographic portrait by Nadar, to the condition of her estate after she passed away. Schopp extends his questions beyond merely ‘Who is she?’ but also to: ‘Where did she spend her childhood? What was her life as a dancer in the Paris opera like? How did she pass her days?’

A second look at the history of L’Origine du monde can help us to better contextualize Shopp’s project. L’Origine du monde is a painting that thrusts the female sexual organ before its viewers. The figure compels viewers to accept an unidealized image of the female sex. Since its first days, L’Origine du Monde, linked to the taboo of female sexuality, has caused anxiety for its male audience. The original owner, Khalil Bey, hid the painting beneath a green curtain and revealed it only for the pleasure (or consternation) of select guests. Lacan, too, hid the painting within a puzzle box, which (tellingly) only Lacan knew how to open. There is a certain poetic justice tied to the painting’s current display in plain view at the Musée d’Orsay. For the first time in its history, the painting requires no mediation. Without its veil, L’Origine du monde gives nothing to mollify the explicit presentation of the female body—no fig leaf or flirtatious gesture conceals her. The woman is at last present.

It is in this context that we receive Schopp’s book. His efforts to apply a name to the faceless figure in Courbet’s painting can be perceived as simply the most recent attempt to soothe the primeval anxieties invested in the work. Through L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, Schopp attempts to undo the mystery of Courbet’s painting with the stated objective of giving a name to the woman’s body. Yet, the identification of the model is just another kind of veil. Schopp’s book uses research, knowledge acquired about the model, to give an illusion of his own degree of access to the woman’s painted body. Just as Khalil Bey and Lacan established control over the figure by controlling the visibility of the painting, Schopp, too, positions himself as the gatekeeper before the work. Rather than humanizing the figure, the information Schopp provides in his book gives a false sense that identity can be encapsulated completely by representation. Furthermore, though Schopp describes Quéniaux’s career as a dancer at length, it is clear that his interest in her derives from Courbet’s painting of her genitalia rather than her achievements in the opera.

When it comes to approaching a painting as provocative as L’Origine du monde, the impulse to research the work may prove irresistible, but the form of interpretation matters. Claude Schopp’s L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle sheds light on the biography of Constance Quèniaux, Courbet’s model and an otherwise unknown woman. However, Schopp’s meticulously researched book serves as just another attempt to establish authority over Quèniaux’s image. The underlying desire to acquire knowledge about Quèniaux, and therefore control, is the true subject of Schopp’s book. For the greater part of its history, Courbet’s L’Origine du monde was hidden in private collections. Now that the painting has found a home in the Musée d’Orsay, it is appropriate to ask: ‘Who is the correct viewer of the work?’ Perhaps it is time to embrace L’Origine du monde as a painting that exists only for itself.

Amber Harper

____________________

[1] See, for instance: Bernard Teyssèdre. Le roman de l’origine(Paris: Gallimard, 1996); Thierry Savatier, L'Origine du monde, histoire d'un tableau de Gustave Courbet, (Paris: Bartillat, 2006). Jr.

The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War

ASATO IKEDA

The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War

Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2018 144 pp.; 33 color ills., 12 b/w.

$60.00

9780824872120

Asato Ikeda’s book The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War offers an important consideration of wartime art. Ikeda, a notable scholar in the field of Japanese art history, often examines the ways that Japanese visual culture intersects with imperialism, war, gender, and sexuality. In her newest publication, she situates 1930s and 40s paintings within the context of Japanese fascism. As Ikeda contends in the book’s introduction, art produced during the Second World War has been largely neglected in Japan. It has only been since the 1990s that scholars have begun critically investigating wartime Japanese art, and almost all of this scholarly attention has been directed toward sensōga, paintings commissioned by the government to record battles. Ikeda instead focuses on paintings that reference Japanese traditions, icons, and culture to reveal the subtle ways that fascist ideology spread throughout Japan in the 1930s and 40s.

Ikeda’s book is comprised of case studies centered on Yokoyama Taikan’s paintings of Mt. Fuji, Yasuda Yukihiko’s Camp at Kisegawa (1940-1941), Uemura Shōen’s paintings of women, and Fujita Tsuguharu’s Events in Akita (1937). Each chapter seeks to uncover the ways that these artworks draw from Japan’s historical and cultural past in order to legitimize the state’s wartime efforts. For example, in “Yokoyama Taikan’s Paintings of Mt. Fuji,” Ikeda argues that Yokoyama’s landscapes resonated with and reinforced Japanese fascism by proclaiming the country’s exceptional cultural identity. Like other fascist governments, Japan’s was characterized by the belief that the country had lost its traditions and “authentic spirit” in the process of modernization. Japanese fascism sought to recreate a national community of people united by the country’s cultural inheritance. Yokoyama drew on the iconicity of Mt. Fuji, a recurring motif in art and literature for hundreds of years, to evoke Japan’s heritage and drum up patriotic support for the government’s efforts to restore Japan to glory.

Ikeda’s exploration of the intersections between fascism and gender in “Uemura Shōen’s Bijin-ga” is particularly compelling. Unlike other scholars who tend to read Uemura’s paintings as anti-war and the artist herself as proto-feminist, Ikeda argues that Uemura’s paintings bolstered the war effort by treating Japanese women as a repository of traditional values, such as self-sacrifice and restraint. For example, the subject of her 1944 painting Lady Kusunoki is a legendary fourteenth-century woman revered for urging her husband and son to fight to the death for the emperor. Ikeda argues that in the context of the Second World War, during which Japanese literature and popular media extolled the honor of women who were willing to sacrifice their sons for the war effort, Uemura’s painting was a highly politicized form of moral education for women.

While each of the case studies is insightful, well researched, and persuasive, the question of artistic agency and intention is not always satisfactorily resolved. In some cases, it is not clear if Ikeda is arguing that the artists were consciously complicit in the spread of fascism. For instance, while Yokoyama’s efforts to raise money for the military and his pro-war writings strongly indicate his support for Japan’s imperialist ideology, Uemura’s personal motivations are more difficult to establish. It would not have weakened Ikeda’s argument to acknowledge the possibility that the artists’ intentions were opposed to those of the state; in either case, their works could act as agents of fascism.

Overall, The Politics of Painting is an important contribution to the literature about wartime art. Ikeda’s skillful analyses of seemingly innocuous artworks reveal the subtle ways that visual culture mediated fascism in Japan before and during the Second World War. Her argument offers a framework for thinking about the ways that ostensibly apolitical artworks participate, either directly or indirectly, in political discourses.

Sara Stepp

Girl in Pieces: The Quasi-Subjectivity of Greer Lankton’s Dolls

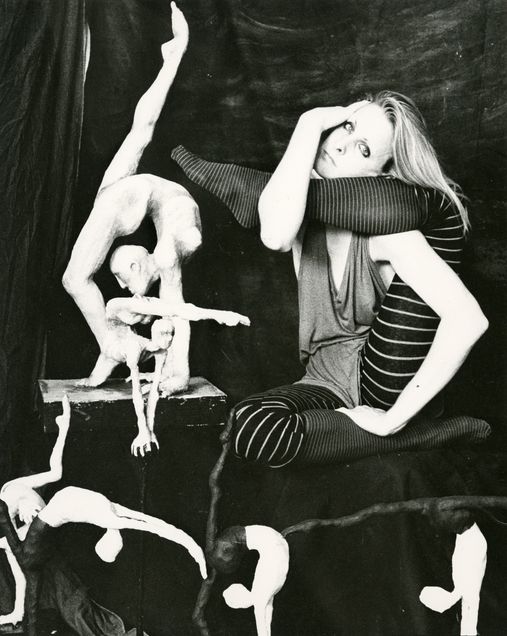

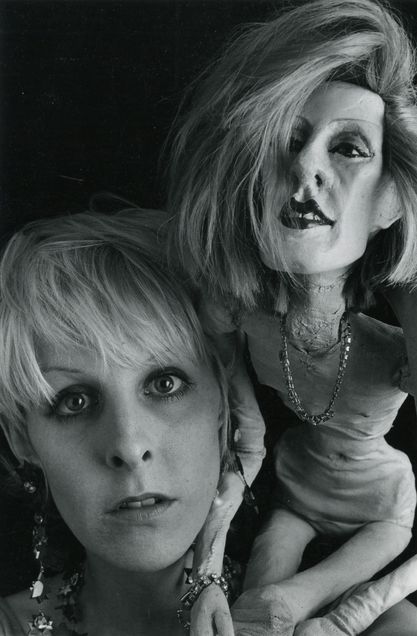

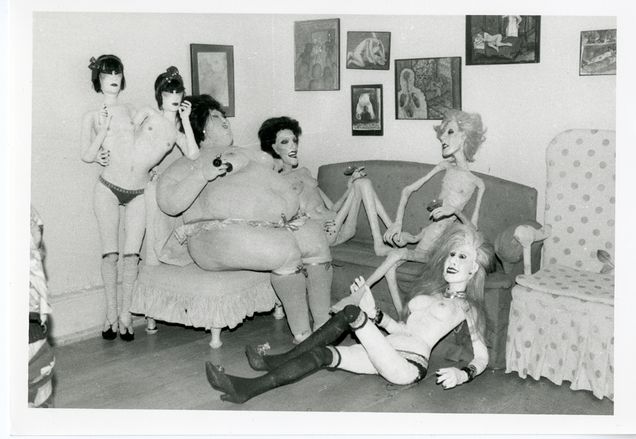

In New York’s East Village in the 1980s, visitors flocked to Einstein’s on East 7th Street to catch a glimpse into the world of Greer Lankton. What distinguished this clothing boutique from countless others were the androgynous, emaciated figures that filled its glass storefront with a kaleidoscope of strange glamour. Made from cloth, wire, and plaster, with glass eyes and real hair, Lankton’s dolls and mannequins had a compelling cult status, situated between art and commerce, high and low culture, beauty and abjection, life and artifice. After her life and career were cut short in 1996 by a fatal overdose, Lankton became marginal to art historical accounts of the 1980s. But as objects that claim some of the qualities of living subjects, Lankton’s dolls embody the fraught relationship between subjectivity and representation that was a major concern of feminist artistic discourse of her period (Fig.1).

Lankton’s dolls can be read as quasi-subjects, on the threshold between person and thing. In their anthropomorphism, they suggest the potential for subjectivity, but more significantly they act as surrogate subjects in the artist’s own production of the self. Unapologetically autobiographical in nature, Lankton’s workis deeply entangled with the politics of transgender representation. Judith Butler has articulated how gender “figures as a precognition for the production and maintenance of legible humanity”[1] within the social sphere. As a transgender woman, Lankton lived with the threat of becoming a “thing” under the normative gaze. Through the quasi-subjectivity of her dolls, the artist destabilizes the very categories of “person” and “thing.” Viewing photographs of dolls posed by the artist, acting as subjects, and of the artist posing alongside them, produces a confusion of subject-object relations similar to what Bill Brown’s study of the “thingness” of objects calls “occasions of contingency” that disrupt clear boundaries of self against Other. “The story of objects asserting themselves as things,” he writes, “is the story of a changed relation to the human subject,” [2] a changed relation that Lankton courts to reframe normative perceptions of bodily difference and gender variability (Fig. 2).

The projective capacities of the doll and its cousin, the mannequin, have been seized upon by many artists across the twentieth century. They embody the mechanized subjectivity of mass culture, the repressed and at times violent impulses of sexual desire, and, later, feminist critique of social conditioning. In the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition, dolls and mannequins embodied “both the femme-enfant, an uncanny childlike doll who evoked repressed fears and desires, and the femme fatale, who evoked lustful and often sado-masochistic fantasies,” according to Alyce Mahon.[3] However, the modernist doll was not exclusively a vehicle for masculine projections of desire, fear, and violence onto the female body. Modernists Sophie Taeuber, Emmy Hennings, and Hannah Hoch all worked with dolls. Hal Foster notes that “for these women, such figures were vehicles of role-playing, of staging and testing models of femininity.”[4]

Of particular resonance to Lankton’s work is the fin-de-siecle dollmaker Lotte Pritzel, who, like Lankton, created her androgynous figures for commercial storefronts and as art objects. Pritzel inspired Rainer Maria Rilke’s now classic essay on the doll, which explored the “doll-soul,” an excess element beyond projected fantasies, that sits on the threshold of human comprehension. He writes, “we realized we could not make [the doll] into a thing or a person, and in such moments it became a stranger to us.” [5] This life of the doll, neither object nor subject, is key to understanding Lankton’s artistic project.

The doll’s potential to destabilize boundaries of subjectivity found its apex in the work of German artist Hans Bellmer, whom Lankton identified as her greatest influence.[6] His painstakingly crafted Poupée, composed of abject torsos and limbs connected by ball-joints, could be assembled in various configurations. While Bellmer’s work has been criticized for its disturbing fixation on the sexualized adolescent female form, the significance of his work here is in his conception of the body as mutable, inviting endless reconfiguration through its “annagramatical potential.”[7] Roxana Marcoci argues that his transformations of the doll “dispensed with the idea of the unitary self,”[8] offering alternatives to normative conceptions of the sovereign body.

Lankton’s dolls show startling parallels to Bellmer’s. Both continuously reworked, repainted, and reassembled their dolls, laboring over them for years. They also shared an obsessive desire to document the transformation and animation of their figures through drawing and photography. Like Bellmer, it is through Lankton’s posed photographs of the dolls, the ways in which she crafted their relationship to the gaze of the camera, that we learn the most about their potential inner life.

Sissy, one of Lankton’s favorite dolls and her most autobiographical figure,[9] was continually reworked for the entirety of Lankton’s career, as seen in photographs spanning nearly a decade. In one image, we see Sissy seated outside Einstein’s, seemingly taking a smoke break. In another, she is shown outside a subway station, wig removed, her pants around her ankles, her penis exposed. Another shows her lounging in a bedroom surrounded by smaller, less animate dolls. Sissy’s style of dress varies in each, as does the painted surface of her body. Previously unpublished photographs from Lankton’s archive show Sissy stripped down to her wire armature, caught in the process of disassembly, revealing the degree to which these revisions penetrated to the doll’s very core. (Fig. 3)

Lankton spoke of Sissy’s reconstructions as her “operations,” ritualized and documented by the camera.[10] Bellmer used the same term to describe his doll’s transformations.[11] In Bellmer’s case this carries an almost sinister connotation, but if Sissy is indeed a self-portrait, Lankton’s use of the term takes on different meanings. Lankton had a history of traumatic medical care in childhood, including electroshock therapy to “cure” her transgender “condition.”[12] Her sexual reassignment surgery at the age of nineteen led to months of traumatic physical recovery, which she documented in harrowing drawings. Here the term “operation” reveals a deep empathy with the position of her dolls, and a desire to reframe her medical trauma as a creative act of transformation.

However, traumatic de-articulation is merely one aspect of Lankton’s project, just as gender dysphoria or transition narratives are merely one aspect of trans life. Her work also exudes a sense of familial intimacy, celebratory glamour, and unflagging humor. In many of the photographs she made of her dolls, she trains her camera on them as intimates, focusing on their faces, their postures, and their interactions with one another. Unlike Bellmer’s photographs of his Poupée, which appear violently coerced into position, Lankton’s dolls seem almost in control of their imaging, knowing and willful collaborators. (Fig. 4)

In his writings on feminist strategies that subvert the masculine gaze, Craig Owens identifies a “rhetoric of the pose” whereby artists adopt posing as gray zone between being passively rendered an object and actively becoming a subject. Owens argues that in such works “the subject posesas an objectin order to be a subject.”[13] To see Lankton’s sculptures as posingrather than posed is to read them as rendering themselves objects. Agency is thus granted to the dolls through their very status as objects, in a formulation related to Lankton’s complex relationship to her own image in the world as a transfeminine body. Barbara Johnson acknowledges that a founding insight of feminist criticism is “that the idealized, beloved woman is often described as an object, a thing, rather than a subject,” but argues “perhaps the problem with being used arises from an inequality of power rather than from something inherently unhealthy about willingly playing the role of the thing.” Instead, she asks: “what if the capacity to become a subject were something that could best be learned from an object?”[14] To extend this to Lankton’s practice, how does this emergence of subjectivity for these surrogate bodies through their very objecthood, their materiality, relate to an experience of trans embodiment?

An answer might be found in Peter Hujar’s portrait of Lankton posed alongside her dolls Sissy and Princess Pamela, shot for her exhibition at Civilian Warfare in the East Village. Reclining nude together, the three present a radical image of the possible configurations of femininity, or even personhood. Lankton entangles the status of her dolls as quasi-subjects with her own precarious status as a “legitimate” body in the eyes of others. She poses herself as if a doll, drawing on their liminal status between subject and object to claim the space of material and gendered indeterminacy as her own. (Fig. 5)

Understanding Lankton’s life entwined with her dolls’ provides us with new codes of intimacy, and new modes of perceiving otherness. To see objects as living subjects, to acknowledge the dissonance in this recognition and nonetheless invest empathy and care towards these objects may help us to live empathetically with difference among subjects. Jane Bennett’s understanding of the life of objects insists on “the alterity of things as an essentially ethical fact,” whereby “accepting the otherness of things is the condition for accepting otherness as such.”[15] Lankton’s dolls invite similar readings, producing considerations of self and other as always in a state of relation and becoming.

Evan Fiveash Smith

____________________

[1]Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (London: Routledge, 2004), 11.

[2]Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 1, Things. (Autumn, 2001), 1-22: 4.

[3]Alyce Mahon, “The Assembly Line Goddess: Modern Art and the Mannequin,” from Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 191.

[4]Hal Foster, “Philosophical Toys and Psychoanalytic Travesties: Anthropomorphic Avatars in Dada and at the Bauhaus,” in Art and Subjecthood,25.

[5]Ibid., 57.

[6]Greer Lankton, artist statement for It’s All About ME, Not Youat the Mattress Factory, 1995.

[7]Marquand Smith, The Erotic Doll: A Modern Fetish.(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 292.

[8]Roxana Marcoci, “The Pygmalion Complex: Animate and Inanimate Figures,” in The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1938 to Today, 186.

[9]Lia Gangitano, as told to Johanna Fateman, “500 Words: Greer Lankton,”Artforum, October 2014.

[10]Paul Monroe, “Unalterable Strangeness,” Flash Art.

[11]Wieland Schmied, The Engineer of Eros, in Hans Bellmer, 22.

[12]Monroe, “Unalterable Strangeness.”

[13]Craig Owens, “Posing,” in Difference: On Representation and Sexuality(New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1985), 17.

[14]Barbara Johnson, Persons and Things (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 95.

[15]Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things(Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 12.

Under a Dismal Boston Skyline

Installation of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

Faye G., Jo, and James Stone Gallery, Boston University Art Galleries, Boston, MA

September 14, 2018 – October 26, 2018

Upon entrance to the exhibition “Under a Dismal Boston Skyline,” on view September 14 - October 28, 2018 at the Stone Gallery, Boston University Art Galleries, visitors are immediately struck with the eerie melody of Nina Simone as part of the projected work by Suara Welitoff, “Be the Boy,” (2001) facing the gallery doors (Fig. 1). In the looping black and white video, we see a young man winking and shaking his hair at the camera in a direct flirtation, which recalls Andy Warhol’s “Screen Tests” of the mid 1960s. But instead of a neutral backdrop, as in Warhol’s performative videos, behind this man attempting to “Be the Boy,” we see an out-of- focus skyline. While no defining landmarks appear, the exhibition title on the wall nearby (along with the thoughtfully written wall label) announces that the cityscape behind the film’s subject is of course, Boston.

Figure 1. Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, featuring Suara Welitoff, Be the Boy, 2001. Courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

Figure 1. Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, featuring Suara Welitoff, Be the Boy, 2001. Courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

This brief film sets the tone for an exhibition which is at once nostalgic and energizing, intimate, elusive and illusive. Although the city of Boston, with its history and its cultural conservatism, is always present in the background, the major protagonists of the show are the figures that have contributed to its rich alternative culture from the late 1970s until today. The exhibition is divided between artists who emerged from Boston and left (such as Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Maura Jasper); those that had only fleeting relationships with the city (including Art School Cheerleaders, Creighton Baxter, Óscar Díaz); some who came, and remained as educators (Marilyn Arsem, Dana Clancy, Bonnie Donohue, Steve Locke); and a couple of persistent locals (Luther Price, Candice Camille Jackson). With work spanning the last four decades, the 25 artists in the exhibition offer representations of themselves, each other, and the artistic counterculture in and around Boston (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

Figure 2. Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

The exhibition provides a hazy portrait of a moment in time in the late 1970s- mid ‘80s when the city was home to an energetic group of students who inspired each other, relying heavily on their communities (often tied to the punk scene, and gay/transgender culture) to fuel their emerging, experimental practices. The unofficial leader of this group was photographer Mark Morrisroe, a Boston-area native, who went to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts where he met several of the other artists connected to The Boston School.[1] Several portraits of Morrisroe are on view: a monumental, eerie, patchwork silhouette by twins Doug and Mike Starn (1985-6); a film featuring the strikingly calm artist describing his survival of a shooting, part of Bonnie Donohue’s Survivors series (1982-3); and two photographs that Morrisroe took himself, one a mischievous self-portrait (1981), and the other, a selfie before its time, made with Morrisroe’s signature “sandwich” print method, which depicts Morrisroe with close friend Gail Thacker (1978/86).[2] These works reveal a playful, yet enigmatic young photographer, lost too early to AIDS, who was worried about being perceived of as “weird,” but was clearly embraced by his creative community. Morrisroe’s significant presence in the exhibition illustrates how the artist’s personal mythology was an important point of connection for those he interacted with directly, as well as those he influenced through his work (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

Figure 3. Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

Morrisroe was part of the impetus for the exhibition – independent curator Leah Triplett Harrington, one of the curators for this show, had been researching the artist when she joined forces with the exhibitions other curators: Evan Fiveash Smith, an M.A. candidate in the History of Art and Architecture at Boston University , and Lynne Cooney, Artistic Director at the Boston University Art Galleries.[3] The team of curators used the Boston School as a starting point from which to look forward from the late 1980s until now, selecting artists who had integrated themselves into Boston’s fabric and whose practices embody similar kinds of experimentation in photography, film, and performance that were initiated in earlier decades.

Figure 4: Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, featuring the work of Steve Locke and Mark Morrisroe, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

Figure 4: Installation view of Under a Dismal Boston Skyline, featuring the work of Steve Locke and Mark Morrisroe, courtesy of Boston University Art Galleries. Photo by Evan Fiveash Smith.

The result is a network of students and teachers, collaborators and strangers, who continue to push the boundaries of filmic media and conformist culture (Fig. 4). While there are certain pieces that connect less obviously with the themes of the show, overall the more recent work provides visitors with the opportunity to familiarize themselves with lesser-known figures. Some of these works share formal similarities, evidenced in the abstracted remnants seen in the slide projections of Luther Price and Genesis Báez’s buried photographs. In other examples, such as the drawings of Cobi Moules and Steve Locke or Esther Solodnz’s painted panels, there is a clear tendency to push away from photographic portraits as representations of identity or selfhood. But in all, the exhibition’s diversity of characters and artwork leaves the viewer with a snapshot of Boston’s cultural underground as it has developed in recent years, urging us to remain aware that under our shared, dismal skyline, captivating experimentation is ongoing.

Sasha Goldman

____________________

[1] Many of these figures were historicized in a 1995 exhibition at the Boston ICA entitled “The Boston School,” which identified common threads in the work of several photographers working in Boston in the late 1970s and ‘80s. Artists from the Boston School included in this exhibition are: Nan Goldin, Shellburne Thurber, Mark Morrisroe, Gail Thacker, and David Armstrong.

[2] Morrisroe developed a method of using a Polaroid Land camera, which he used to create the technique of mounting enlarged double negatives on top of each other.

[3] Conversation between Lynne Cooney and the author, October 11, 2018.

Editors’ Introduction

This issue of SEQUITUR brings to readers work on multiple, multifaceted, and overlapping concepts of “text/ure.” Through a focus on the element of texture itself as a material quality of surface, we hope to deliberately emphasize haptic experience in the contents of this issue, rather than limiting exploration to the optic realm, so frequently privileged in art-historical discourse. Further, by highlighting textual elements of the works examined in this issue, which some of our authors have chosen to treat with semiotic methodology enjoying revived popularity in scholarship of the digital age, this issue acknowledges the textured encounters between these works, their makers, and their viewers.

Our feature essay, by Anni Pullagura, delights in the possibilities of such material and semiotic convergences. She approaches the haptic qualities and aesthetic tensions “embodied” by the spectral, sculptural works of contemporary artist Kevin Beasley, who uses aural feedback networks to give “voice” to his resin-drenched figures.

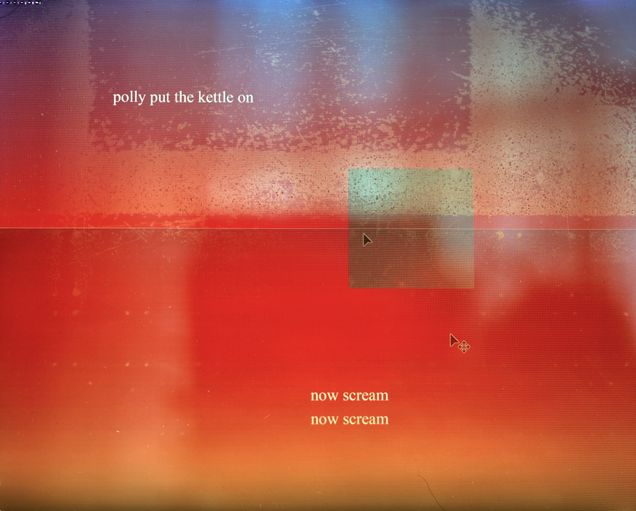

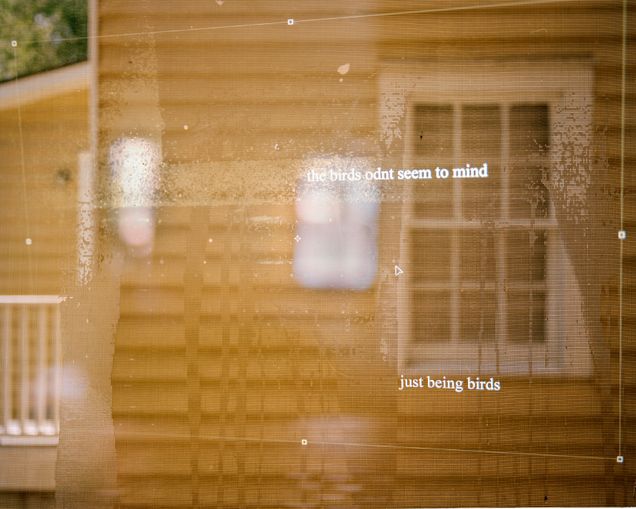

Julia Wilson’s visual essay explores a related and twofold form of aesthetic strain. She does this by first remixing photographic images with fractured text, then, by capturing the digital product with a large-format camera. This method calls attention to the existence of the computer screen as both container and medium, in turn pushing against the boundaries of how viewers perceive both surface texture as well as the relationship between text and image as it unfolds across that surface.

The two research spotlights in this issue examine the relationships between materiality, function, and meaning while dealing with issues of the history of race in America in some capacity. Mariah Gruner’s work on an early-nineteenth-century cradle quilt demonstrates how the “soft politics” of white American women abolitionists manifested themselves within and beyond the world of needlework. Kate Sunderlin’s field report from the studio of Edward V. Valentine, a Richmond-based sculptor who held some troubling views on racial equality, explores the ways in which a group of plaster sculptures of African Americans entered into dialogue with other plaster works present in the studio where they were displayed.

Althea Ruoppo’s interview with Mitra Abbaspour and Calvin Brown, co-curators of Frank Stella Unbound: Literature and Printmaking, reveals that the artist’s graphic oeuvre used and interpreted narratives through abstract forms. Here, we learn how the relationship between text and image is pushed to encompass not just a response to, but an alternative expression of those literary forms after which Stella named his print series.

Both of the exhibition reviews, Sasha Goldman’s on Under a Dismal Boston Skyline and Alex Yen’s on Animal-Shaped Vessels from the Ancient World, round out our issue by reporting on the ways in which curators are demonstrating the textual, social-historical, and material connections that exist within and among groups of historic works

Overall, the contents of this issue intends to leave the reader with a richer understanding of how the element of texture can be conceptualized in a way that enriches and complicates our understanding of a given work or group of works in a way that reaches far beyond mere surface.

The Editors would like to take this opportunity to extend a special thank you to everyone who has had a hand in the redesign of our journal's website, especially to Susan Rice for her tech support, Morgan Hamilton for his coding expertise, Isaac Goldman for the design of our new logo, and our Senior Editor Kimber Chewning for her initiative, leadership, and enthusiasm throughout the process.

Ali Terndrup

Plaster and Process – The Studio of Edward V. Valentine

Plaster sculptures appeared in nineteenth-century homes, studios, museums, and schools, and their use and reception varied in each of these contexts. My dissertation considers the works of two American artists, both of whom worked with and displayed plasters in their studios, and had close ties to the museums displaying plasters to a wider public. To illuminate the roles and uses of plaster in the sculptor’s studio, I examine the studio of Richmond-based sculptor Edward Valentine (Fig. 1). The plaster cast collection of the Valentine Museum (founded by Edward’s brother) will be examined in order to understand plaster’s function within the public museum. By closely analyzing Valentine’s correspondence, works, and related documents (such as contracts with clients or foundries), I reveal not only the role of plaster in his process, but also the professional ecosystem that existed to support and create his work. In turn, this case study tells us about the use of plaster and the practices of plaster-modelers in the period more broadly. My research thus far has revealed professional ties to other sculptors and plaster-modelers in both Richmond, Virginia and New York City.

I also consider how Valentine, his clients, and visitors to his studio felt about the use of plaster aesthetically through anecdotal evidence, personal correspondence, and newspaper articles. How did viewers approach plaster objects in the artist’s studio? What can their impressions tell us about larger sociocultural and political trends or beliefs? One example of the outcome of such inquiry comes from the chapter I am currently writing, a section on Valentine’s series of plaster sculptures of African Americans – The Nation’s Ward, Knowledge is Power, and Uncle Henry (Ancien Regime) – a challenging subset of his oeuvre (Figs. 2, 3, and 4, ). All three works reveal not only Valentine’s own personal racist sentiments, but also the pervasive racism and bigotry of the era, evidenced in the sculptural narrative and formal qualities of each piece.

Race as a concept underwent profound development during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One of the most pernicious attempts to establish a racial hierarchy came from the measurement and comparison of crania, particularly the work of Pieter Camper. Diagrammatic charts published alongside his lectures seemingly presented a hierarchy of mankind from ape to Apollo, with the European next to the Greek god, and the African next to the ape (Fig. 5). That the Apollo Belvedere was chosen to represent the highest visual ideal is significant. In his Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks (1755), Winckelmann argued that Classical sculpture should serve as a model for modern artists, especially in learning to capture the ideal – the emotional, intellectual essence and perfected physical form of a subject – devoting a particularly effusive passage to the Apollo Belvedere. Despite the fact that there was early evidence for the use of polychromy by the Greeks and Romans, whiteness remained an important aspect of Winckelmann’s ideal and it was about more than just sculpture’s emphasis on form. That plaster is inherently a white medium cannot be overlooked and its whiteness in conjunction with its use to reproduce the classical sculptural canon, a canon now closely linked to Europeans, reinforces the linkage of white racial superiority to the classical tradition privileged Euro-American institutions of arts and education.

Valentine’s first work cast in plaster was a copy of the bust of the Apollo Belvedere in his father’s home, itself a reproduction. In copying from this sculpture, Valentine became part of a larger Euro-American academic tradition that privileged Classical statuary. Furthermore, owning and displaying such a copy was meant to exemplify his perceived social, racial, and intellectual superiority from which his elite status as a member of Richmond’s high society was derived. As a result, Valentine kept it in his studio for the rest of his life. Thus, this copy and his three sculptures of African Americans would have been in visual dialogue in his studio, reproducing in three dimensions Camper’s damning diagrammatic chart.

While the depressed economic climate in the South immediately after the Civil War kept the commissioning of monumental marble or bronze public sculpture at bay, it did support the production of portrait busts and figurative sculpture cast in plaster and sold commercially. Plaster’s whiteness demanded that the subjects’ blackness be made visible in other ways (or doubly visible when painted). The half-length bust of The Nation’s Ward depicts a young African American boy wearing worn clothing and a military cap, part of a Civil War uniform. When visiting Valentine’s studio, two ladies visiting from the North viewed the piece and one “said what a pretty name and sentiment it was, but on conversing with a Southern gentleman found it was meant as a satire.” Valentine has relied upon the use of stereotypical features “such as thick protruding lips, flared nostrils, and kinky hair” to identify this figure as a person of black African descent. This work is an example of a racist caricature, the picaninny, extremely popular at the time and for most of this country’s history. By drawing upon the character of the picaninny, Valentine is reinforcing the stereotype of African Americans as lazy, often portrayed in cartoons of the era as comical in their indolence and ignorance. He seems to be making a cruel joke at their expense, masked as “good humor,” ridiculing what he and others perceived as their misguided reliance on the Federal government in the postwar era. It was Valentine’s bigoted and bitter answer to the national debates over the work ethic of and economic opportunities for the nation’s recently freed African American men and women, amusing only to other bigoted elite white viewers. Plaster’s versatility and affordability allowed for the replication of imagery, from the Classical ideal to the modern caricature, and all its attendant ideologies, from the implicitly to explicitly racist.

Kate Sunderlin

Soft Politics: The Frictions of Abolitionist Women’s Needlework

Textiles are thought to be soft objects, saturated with care and memory. Present at our most vulnerable moments, they dab at tears, wipe up messes, swaddle fragile bodies, cover nakedness. The weight of a quilt comforts us, its formal familiarity promises continuity. I investigate the persistence of these textile narratives, their alignment with cultural constructions of femininity, the status of the implicit woman behind the cloth, and their discursive deployment. I research women’s decorative needlework in the United States and its relationship, in the cultural imaginary, with softness, sentiment, and nostalgia. What has sedimented in embroidery, as a medium, technique, and discursive construction? What frictions are embedded in the relationship between its cultural construction, its use, and its strategic deployment? In “Soft Politics: The Frictions of Abolitionist Women’s Needlework,” a chapter from my dissertation, “ I examine the work of white women in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s-1850s in order to explore these broader questions of the political meanings of work so consistently read as paradigmatically outside of the realm of both “work” and “politics.” This essay outlines my initial research into this portion of my dissertation project.

Even by the 1830s, needlework was understood as a nostalgic icon of the home, a representative of naturalized “women’s work” (unwaged, but thought of as an outpouring of love), a practice associated with an imagined, pre-industrial past. Needlework practice and discourse in the nineteenth-century aligned women’s embroidery with the images of the “Colonial Goodwife” and the “Republican Mother,” simultaneously celebrating women’s national influence as mothers and moral actors and establishing a discourse of separate spheres. This discourse created a conceptual framework that worked to bound that influence within the home (both as a literal space and a conceptual one, constructed in opposition to the notions of the public as a space of overt politics, fast pace, transactionalism, and masculinity). I argue that women also used this framework to make space for themselves, infusing their “domestic” textiles with political weight, public commentary, and market-savvy aesthetics. They used softness as a tool of puncture.

In “Soft Politics,” I work with women’s antislavery textiles to understand the complex dynamics of their deployments of femininity, softness, and domesticity in a political movement that, at best, uneasily incorporated women as participants. The American Anti-Slavery Society split in 1840 over the question of women’s full participation and the first women’s rights convention in 1848 was planned in response to the exclusion of women delegates at the London World Antislavery Convention.[1] Yet women continued to participate in the abolitionist movement as speakers, fundraisers, writers, and even organizers and members of their own antislavery societies, sewing circles, and antislavery fairs. Women’s fair and fundraising work was a key source of income for the antislavery movement through the 1840s and 1850s, one that enabled their political participation while maintaining associations with domestic feminity.[2] These fairs were sophisticated operations, organized by large committees of women and featuring, for sale, “domestic crafts” that otherwise would have been understood as products of the unremunerated labors of a refined, genteel woman, rather than politicized objects or objects sold for compensation. The sale of handkerchiefs, needle books, fancywork embroidery, workbags, and other crafts at antislavery fairs and bazaars gave women the opportunity to see themselves as political actors and earners, while still drawing on the associations with domesticity, morality, sewing circles, and women’s “benevolent work.”[3] These fairs confirmed both the economic value of women’s domestic (“ornamental”) pursuits and their political force; many of the objects sold both materially and aesthetically announced their makers’ (and purchasers’) political commitments.[4] Among these objects is a cradle quilt, sold at the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Fair in 1836. Although the object is not signed, it corresponds to a quilt that Lydia Maria Child described making and selling at this fair, suggesting a lineage in the hands of one of the great abolitionists of the early nineteenth century.[5]

As part of a research trip supported by a grant from the Decorative Arts Trust, I spent portions of the summer of 2018 traveling to the archives at Historic New England, the Peabody Essex Museum, and Colonial Williamsburg to examine abolitionist textiles (figures 1 & 2). At Historic New England, I encountered this quilt, stitched in an unassuming, classic Evening Star motif. The quilt, a cradle quilt meant for a child’s bed, is small (measuring only thirty-six by forty-six inches) and closely worked in fine hand-stitching. Its colors are muted and soft, an accumulation of printed cotton blocks in pink, blue, and brown star patterns; at first glance, this is not a remarkable quilt. However, the maker clearly played upon the quilt’s anticipated home in a cradle, using the implied anticipation of a maternal, sentimental scene as an occasion to insert an overtly political message. Delicately inked in the quilt’s central star is a hand-written stanza from Eliza Lee Cabot Follen’s poem, “Remember the Slave”: “Mother! When around your child/ You clasp your arms in love./ And when with grateful joy you raise/ Your eyes to God above,-/ Think of the negro mother, when/ Her child is torn away,/ Sold for a little slave- oh/ For that poor mother pray!”

This poem demonstrates the political stakes threaded through the maternal relationship and the domestic scene, asking women to consider the contrast between their moments of relative domestic serenity and the fundamental cruelties of enslavement.[6] It harnesses the softness of the quilt and contrasts it with the puncture of political commentary. Although the poem does go on to extend sympathy to “the poor young slave,/ Who never felt your joy,” the stanza that marks this quilt implicitly questioned the scene of white domestic love and pleasure, asking its players to consider whether it was grounded on the exploitation and exclusion of others.[7] The quilt asks those who encounter it to split their consciousness, countering the notion that quilts, or textiles in general, serve to wrap up, to hold, to comfort.

Angelina Grimké, one of the only white Southern women known to have joined the abolitionist movement, literalized the textural dimension of this form of textile activism in the antislavery movement in her writings.[8] In her “Appeal to the Christian Woman of the South, Grimké wrote of the layered work done by women in anti-slavery societies, bringing together notions of moral work and physical labor in her descriptions of the creation of antislavery crafts for sale at fundraiser fairs.[9] She helps confirm that women’s antislavery crafts often involved the physical representation of the body of an imagined enslaved person, writing that women were “telling the story of the colored man’s wrongs, praying for his deliverance, and representing his kneeling image constantly before the public eye on bags and needle-books, card-racks, pen-wipers, pin-cushions, &c. Even the children of the north are inscribing on their handy work, ‘May the points of our needles prick the slaveholder’s conscience.” Her writings consistently highlighted the ways in which women might remake political debate by centering their own cultural construction as moral, religious anchors of the home; their domestic position, ironically, became the justification for their emergence into the public sphere. In her discussion of abolitionist women’s craft work, Grimké deftly wove together Christian morality, maternal influence, textile production, public presence, and the textural contrast of the needle through cloth to evoke the force of the political commentary of “innocents.”

My work considers the active construction of the “innocent” subject position, its relationship to the supposed benevolence of textiles, and the limits of its political salience. In the context of the early nineteenth century, “innocent” was a subject position foisted upon both women (“protected” from the exigencies of the political and economic worlds by the system of coverture) and children, a signal of their dependence and, therefore, justification for their exclusion from full civic identity. However, it could function as a strategic claim of women and children (typically, white women and children, although abolitionists also worked to extend this category to black women and children). By announcing their sentimental purity, their status as “moral mothers,” women justified their political platforms. But my research questions both the racial dynamics of these claims and whether they helped reify or undermine gendered associations between femininity, domesticity, and depoliticized existence. Though I have found a few interesting examples of ornamental needlework by African American women during this time period and do not wish to whitewash the abolitionist movement, the majority of women participating in these specific antislavery craft practices were white. In these women’s hands, what (or who) did the cradle quilt’s contrast between the white, loving, domestic mother and the black, bereft, laboring mother serve? These makers exploited the friction of juxtaposition, contrasting the sharp puncture of their needle and message with the maternal embrace of the quilt, the femininity of the decorative stitch. This formal contrast undergirded a second juxtaposition, one between their own white status and that of enslaved persons. But this second juxtaposition of status also served as a point of comparison, an occasion for white women to call attention to their own unremunerated labors, their own exploited states.[10] What did this frictive layering generate?

This fundamental question has led me to consider the politics of white sympathy and the commonplace notion that the abolitionist movement was the political staging ground for the women’s suffrage movement. Read through this historical lens, it becomes all the more important to think through the meanings of women’s politicized crafts and their relationship to gendered visions of race and raced visions of gender. At Colonial Williamsburg’s archives, I examined an undated, unsigned sampler that features a stitched iteration of the classic Josiah Wedgwood antislavery seal. A woman stitched the image of a kneeling, chained enslaved person in the fashionable, though solidly middle-class “Berlin work” style. This image was a mainstay of abolitionist visual rhetoric, but women also “feminized” the scene, stitching and printing an enslaved woman with the text, “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?.” A small needle-case at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, bears this feminized iconography, an enslaved woman kneels at the feet of an allegorical figure of justice (functionally, a white woman). Though these objects were very real actors in the cultivation of a feminine antislavery movement and enabled women to understand their domestic crafts and decorations as politically relevant, they raise questions about the creation of images of black suffering by white women. As these women stitched their fashionable samplers, pulled needles out of cases printed with classical emblems, and carried workbags signaling their moral, cross-racial sympathies, they developed their own networks, sentiments, and senses of self, revealed in the public sphere.

My work takes these objects and practices seriously, thinking through what it might have meant to labor over the construction of the image of a suffering, black body (as did the maker of the Colonial Williamsburg sampler), what it might have meant to wrap one’s child in a quilt infused with the reminders of the loss, violence, and injustice attending other domestic scenes (as Lydia Maria Child did). But I also hope to question what it meant for white women to construct these images in service of developing their own political subjectivities. How was needlework’s associations with softness, nostalgia, and femininity deployed in each of these contexts? And to what ends? What can histories of women’s decorative needlework production help us understand about abolitionists’ uses of these tools? My research considers these textures of women’s political textiles, tracing the histories sedimented within them, their accreted associations, what they smooth over, and what they help puncture.

Mariah Gruner

____________________

[1] Henry Mayer, All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1998), 82.

[2] Alice Taylor, “‘Fashion has extended her influence to the cause of humanity’: The Transatlantic Female Economy of the Boston Antislavery Bazaar” in The Force of Fashion in Politics and Society: Global Perspectives from Early Modern to Contemporary Times, ed. Lemire (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010), 118.

[3] Of course, this calls us to recognize the class dimensions of these fairs. Many women did already see themselves as workers and were paid for their labors (although they themselves could not legally own property or enter into a contract), but these were typically not the same women who did fancy needlework at home.

[4] This is particularly important given the fact that the laws of coverture meant that married women could not own property. It enabled women to see the economic value of their domestic pursuits, which otherwise were typically unremunerated. Indeed, advertisements for the Massachusetts Antislavery Fair in 1839 claimed “Never was there a finer display of money’s worth, whether the purchaser be in search of the useful or the beautiful!,” framing these women’s works as valuable goods. For more, see “The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Fair” The Liberator 9 (November 1, 1839): 44.

[5] Lynne Basset writes that Lydia Maria Child reported, in a letter from January 1837, that her cradle quilt sold for $5.00 and was purchased by Francis Jackson, for his daughter, a member of the Boston Female Antislavery Society. See Lynne Bassett, Massachusetts Quilts: Our Common Wealth (New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2009), 177.

[6] As I noted previously, this quilt is made from printed cotton blocks. Given the importance of cotton as one of the key products of the slave labor system, it is surprising that Child would have used this material without considering its inherent violence. Many abolitionist women worked to boycott cotton, sugar, and other exports of the plantation south.

[7] Eliza Lee Follen, “Remember the Slave,” Hymns, Songs, and Fables, for Young People (Boston: Wm. Crosby and H.P. Crosby, 118 Washington Street, 1851; Project Gutenberg, 2005) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16688/16688-h/16688-h.htm.

[8] Angelina Emily Grimké Weld and her sister, Sarah, left the slave-holding plantation they’d grown up on and moved to Philadelphia in the 1820s, where they became members of the Philadelphia Female Anti- Slavery Society. The sisters eventually became agents for the American Anti-Slavery Society, giving lectures about the evils of slavery and the moral rectitude of the antislavery cause. They insisted on the relationship between women’s rights activism and antislavery work, insisting on women’s rights to speak publicly on political issues.

[9] Angelina Grimké’s 1836 letter is cited in Alice S. Rossi, The Feminist Papers: From Adams to De Beauvoir. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1973), 303.

[10] Indeed, early articulations of (again, white) women’s right to suffrage and property ownership aligned their status with that of enslaved people. They claimed their right to full citizenship and enfranchisement through comparing (and sometimes collapsing) their own treatment with that of chattel slavery, proclaiming the obvious immorality of this state. See, for example, Harriet Taylor Mill, Enfranchisement of Women, (Syracuse, NY: Master's Print, 1853). This metaphorical language exists earlier and continues even in contemporary conversations, as evidenced in the marketing campaign for the recent film, Suffragette, which featured t-shirts with the text, “I’d Rather Be A Rebel Than A Slave.”

Animal-Shaped Vessels from the Ancient World: Feasting with Gods, Heroes, and Kings

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

September 7, 2018 - January 6, 2019

Hey drink, drink, drink, everybody pour me another- Lil Jon, “Drink” from Party Animals

Nunc Est Bibendum (now is the time for drinking)- Horace, Odes

Never has the “party animal” been so at home in the world of art. Currently on view at the Harvard Art Museums, Animal-Shaped Vessels from the Ancient World: Feasting with Gods, Heroes, and Kings celebrates the conviviality and creativity of drinking containers. The exhibition, on view through January 6, 2019, displays seventy-five objects spanning four-thousand years. The vessels vary in terms of time period, geography, form, and material, but they all share a common function: as receptacles used for celebratory, ritualized drink.

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are greeted with two vessels from two cultures: a sixth-century BCE Etruscan vase shaped like a siren and a fifth-century BCE bronze ritual vessel from China shaped like a duck (Figs. 1 and 2). Elsewhere in the gallery, two vitrines display a seventeenth-century gilded automata in the shape of a stag and a fifth-century BCE terracotta vessel with a crocodile side by side. The seeming disorder proves intentional and effective; by placing these objects within close proximity, the careful installation demonstrates the formal and material similarities across time and space: an interest in predators, mythological beasts, and horned creatures as favorites on drinking containers.

A closer look at these vessels brings their materiality into focus and showcases the creativity and skill of artists. The surface of a twentieth-century Cameroonian drinking horn features intricate, patterned carvings. The horn then tapers off into a three-dimensional beaded, figural head (Fig. 3). In other instances, such as an Athenian fifth-century BCE drinking mug in the shape of an eagle head, the artist decorated the exterior with a variety of patterns, from scale-like feathers, to delicate white lashes around the eyes, and a beak with purple, red, or white brushstrokes. The show also includes a small selection of other visual and material culture that contextualizes the ubiquity of drinking. In Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Women of Amphissa, Greek women awaken in the marketplace after a night of carousing and celebrating the god of wine, Dionysus. A stone panel from a Qi dynasty funerary bed displays a scene where divinities feast and drink together in a world beyond the living.

Yet the greatest strength of this show is surprisingly not how drinking vessels relate to gods, heroes, and kings, but rather how they relate to humans doing very human things. From the gilded silver rhtyon (drinking horn) ostentatiously showing off the wealth of the fourth-century Achaemenid empire to the oldest object in the exhibition, an Assyrian bibru (drinking vessel) artfully molded into the shape of a leopard, animal vessels continuously reassert how humans used objects to connect themselves to one another through humor, skill, culture, and drink. As anthropologist Michael Dietler proposed in his opening lecture for the exhibition, the act of drinking represents an “embodied material culture” used by groups to cement very human ties and relationships.[1] Animal-Shaped Vessels uses objects to bind cultures, people, and places together with the inherently communal act of sharing a drink.

Alex Yen

Download Article

____________________

[1] Michael Dietler, “Liquid Material Culture: Anthropological Explorations of Alcohol and Drinking Vessels,” (lecture, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, September 6, 2018).

Visual Essay

This body of work explores our relationship to images, especially with increasing technological access, and our current blindness to the photograph itself -- when images are forgotten as representations and mistaken for reality.

Using a large format camera, I photograph composed images, words, reflections, and grit, contained within my personal computer screen. The clearly visible surface of the screen redirects the viewer’s attention from what the photograph is representing (the subject) to the unintended and overlooked attributes of the medium—surfaces, context, and materiality. The proximity of image to text placed together on a screen mimics how we are accustomed to seeing words in relation to imagery in the everyday – media, advertisements, billboards, cell phones, laptops, and so on – and then disrupts it. Text and image become linked with uncertainty, creating a relationship between the two that is not caption nor definition nor reference; the ever growing, shifting, and changing screen, becomes static. In this, I attempt to de-familiarize our cultural atmosphere by exaggerating it, foiling it. By breaking apart and reassembling these systems of communication, my work makes visual the ambiguities of both image and text, and their material context to recognize the hidden process of individual interpretation in the reception of photographic and photo-textual information. All of these images are fragmented experiences of my life, reformed and manifested into a final image, but nevertheless their interpretation is not confined to that. Through this work, I hope to demonstrate the very conscious decisions we are able to make, when we truly pay attention, in constructing meaning from language and experience.

Julia Wilson

Frank Stella Unbound: Literature and Printmaking

Born in Malden, Massachusetts, Frank Stella attended Phillips Academy, Andover, and continued his studies at Princeton University, in Princeton, New Jersey, earning degree in history in 1958. A painter, printmaker, and sculptor, Stella is one of the most accomplished and prolific artists working today, celebrated for his constant self-reinvention and fearless drive to push the assumed limits of abstraction.

Frank Stella Unbound: Literature and Printmaking (May 19 – September 23, 2018) was organized to commemorate the 60th anniversary of Stella’s graduation from Princeton. It is the first exhibition to focus exclusively on the fundamental role that published narratives played on the artist’s graphic oeuvre. Frank Stella Unbound explores a widely innovative period of Stella’s printmaking career, between 1984 and 1999, when he executed four consecutive print series — Illustrations after El Lissitzky’s Had Gadya (1984), Italian Folktales (1988-89), The Moby Dick Prints (1989-93), and Imaginary Places (1994-99) — each of which was named after a distinct literary work.

While serving as the intern in the Director’s Office at the Princeton University Art Museum during the summer of 2018, I had the opportunity to interview the exhibition’s co-curators, Mitra Abbaspour, Haskell Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Calvin Brown, Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings. During our conversation on August 8, 2018, Mitra and Calvin discussed a number of important considerations in Stella’s work: the interplay of text and image, as it relates to Stella’s interdisciplinary approach and with regard to exhibition display and label copy; the artist’s working process and the incredible range of innovations he introduced to printmaking; the tension between pictorial and material surface texture; and, ultimately, the narrative potential of abstract forms.

Watch my full interview here:

Frank Stella Unbound: Literature and Printmaking is currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville (October 6, 2018 – January 13, 2019).