Population Health Science and the Conditions That Make People Healthy.

I have reflected previously on a definition of public health that I like, suggesting that public health is about assuring the conditions for people to be healthy. I have since been engaged in discussion with some of our faculty about the robustness of this definition, a challenge that had first been taken up in print by our faculty in a provocative paper published in the American Journal of Public Health more than 20 years ago. The central critique of public health’s defined role as that of assuring conditions for people to be healthy is that such a mission is too broad, and that it extends the remit of public health to areas that are more typically the domain of social justice.

I have reflected previously on a definition of public health that I like, suggesting that public health is about assuring the conditions for people to be healthy. I have since been engaged in discussion with some of our faculty about the robustness of this definition, a challenge that had first been taken up in print by our faculty in a provocative paper published in the American Journal of Public Health more than 20 years ago. The central critique of public health’s defined role as that of assuring conditions for people to be healthy is that such a mission is too broad, and that it extends the remit of public health to areas that are more typically the domain of social justice.

In a future Dean’s Note, I will comment a bit further about how I think of the intertwined roles of public health and social justice. Here, however, I wanted to comment briefly on another reason why I like this definition: my concern that population health science simply has no choice but to consider the conditions that shape the health of populations if we are to accurately fulfill our mission of understanding the drivers of population health. This argument rests on recognition of the centrality of—synonymously—“context,” “circumstance,” and “conditions” to population health science, and on recognition that unless context is taken into account, inference we draw from population health science can be wrong, or, worse yet, dangerously misleading.

Context and Population Health Science

μ

Context, Experiment, and Observation

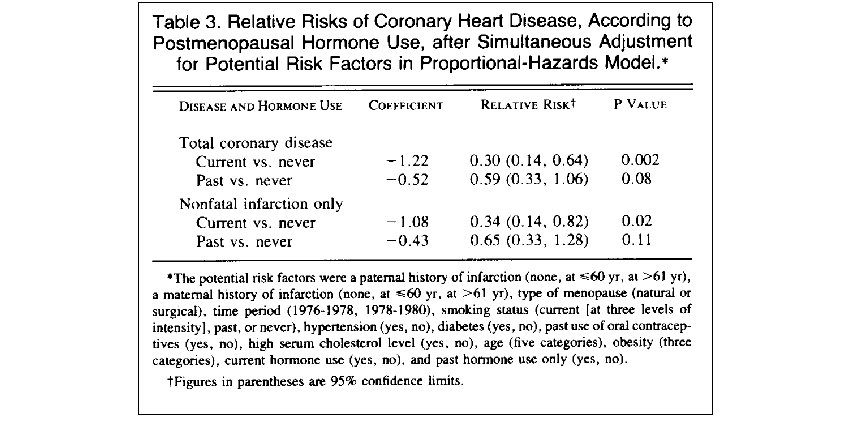

The truth, however, is much more complicated, and comparisons of results from observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide an illuminating window into the central role of context in public health and its study. Classic observational studies such as the Harvard Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) have identified treatment effects of critical interest to public health practice, only to be robustly contradicted by data from RCTs. One now well-worn example is that of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women. The NHS found in 1985 that HRT (i.e. exogenous estrogen) was protective against coronary heart disease at four-year follow-up [see figure 1, below], later reconfirming this finding at 10-year follow-up, and bolstering the continued proliferation of HRT in postmenopausal women.

Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of postmenopausal estrogen therapy and coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985 Oct 24; 313(17): 1044-9.

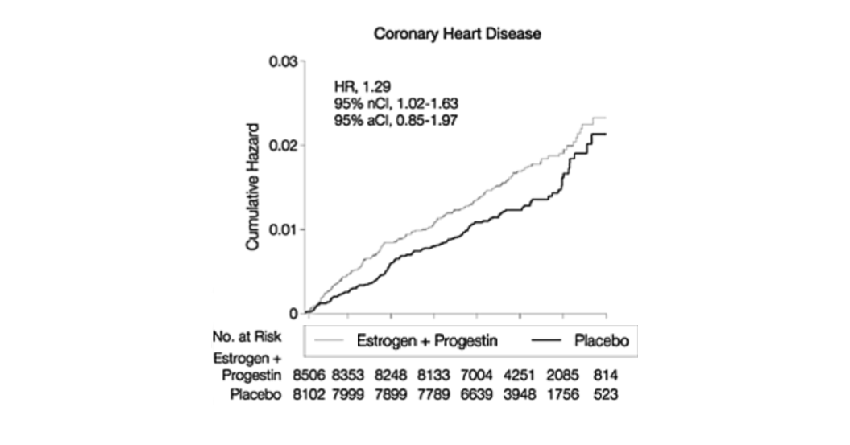

In 2002, these observational findings were robustly contradicted by the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which found, based on their five-year placebo-controlled RCT, that HRT was associated with greater risk of coronary heart disease [see figure 2, below].

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288(3): 321-33.

A similar example is that of beta-carotene for prevention of lung cancer. In 1986, a case-control study of beta-carotene and lung cancer found that people with low levels of serum beta-carotene had approximately four times the risk of lung cancer relative to those with high levels. Again, in a striking about turn, the New England Journal of Medicine published a 1996 paper, based on the results of a large five-and-a-half-year placebo-controlled RCT, that found that beta-carotene was associated with a slightly higher risk of lung cancer relative to placebo.

Explaining the Differences Between Experiment and Observation

Wh

The Inextricable Role of Context, Or Why Conditions Matter

Th

Does this then justify public health being about the conditions that make people healthy? That, to my mind, is a larger question, and one of relative values and priorities. It does, however, make it clear that the conditions that shape populations are unavoidable if we are interested in generating a science of consequence, and a scholarship that stands the test of time.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

@sandrogalea